Despite the persisting unfashionability of guitars in mainstream music, guitars are too versatile and adaptable to ever go away. And while electric guitars may never be as ubiquitous in households as pianos at their peak or even acoustic guitars, as I mentioned in my last piece, sales have grown 72% since 2009 to 1.41 billion. Even video games like Guitar Hero and Rock Band have inspired people to learn the real instrument. Enrollment in the School Of Rock has grown to over 17,000, while thousands of other music camps now include guitars, something that certainly wasn’t a thing when I was at band camp.

It’s not just kids going to camp — on July 30 to August 2, you can attend Camp Fuzz with Dinosaur Jr.. If it weren’t so expensive, I’d be tempted, though somewhat embarrassed, to go. Dinosaur Jr. was the band inspired me to really focus my listening on the guitar. During my first week of college I ended up in the hospital with a collapsed lung for ten days, and You’re Living All Over Me was constantly playing on my Walkman, as I got lost in J. Mascis’s mega-distorted solos. I have no doubt it would be fun, and it will likely sell out. Camp Fuzz is just one in a series put on by Music Masters Camps, based in the Catskill Forest Preserve, east of Woodstock in upstate New York.

I consider most guitars nice to look at. Some are considered more than cultural artifacts, but actual works of art. Just as I had finished Brad Tolinski & Alan di Perna’s book Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar (2016), the Play It Loud exhibit opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 8 to October 1. It seems to focus on the significance of guitars that were played by well known players, but it’s a good start.

While the exhibit features more instruments than just guitars, I can see why it named itself after the Play It Loud book. No other instrument is a more iconic representation of popular music in the second half of the 20th century than the electric guitar. I can’t imagine anyone more qualified to write such a book than Brad Tolinski, editor in chief of Guitar World for 25 years, and Alan di Perna, longtime contributor to Guitar Player, Guitar Aficionado as well as Guitar World. The well-researched book goes deep into the stories of key guitar makers, and players who helped push the innovations. The story starts with George Beauchamp’s and John Dopyera’s early efforts at making guitars loud enough to overcome crowd noise, loud drums and amplified vocals with the tri-cone, three spun cones attached to bridge in 1926. The machinist they outsourced their nickel bodied guitars to, Adolph Rickenbacker, added further innovations resulting in the A-25 Frying Pan, which hit the market in 1932.

While the exhibit features more instruments than just guitars, I can see why it named itself after the Play It Loud book. No other instrument is a more iconic representation of popular music in the second half of the 20th century than the electric guitar. I can’t imagine anyone more qualified to write such a book than Brad Tolinski, editor in chief of Guitar World for 25 years, and Alan di Perna, longtime contributor to Guitar Player, Guitar Aficionado as well as Guitar World. The well-researched book goes deep into the stories of key guitar makers, and players who helped push the innovations. The story starts with George Beauchamp’s and John Dopyera’s early efforts at making guitars loud enough to overcome crowd noise, loud drums and amplified vocals with the tri-cone, three spun cones attached to bridge in 1926. The machinist they outsourced their nickel bodied guitars to, Adolph Rickenbacker, added further innovations resulting in the A-25 Frying Pan, which hit the market in 1932.

The first big name guitar hero of the era of the electric guitar was Charlie Christian. A buddy of influential Texas bluesman T-Bone Walker, he was blowing people away in the jazz scene in Oklahoma City, until he was recruited by Benny Goodman in 1939. Soon, the Gibson ES-150 (Electric Spanish) became Charlie’s main axe, and the popularity of both guitar and player exploded, despite the fact that they were only just emerging from the Great Depression, and $150 was a heck of a lot of money. Meanwhile in California, a friendship between Les Paul, Leo Fender and Paul A. Bigsby (who had a background in motorcycle and industrial design) would result in further innovations.

As Les Paul became a successful performer, he would later end up hanging out with fellow guitarists at the Epiphone showroom in New York, which sometimes included Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt. They’d talk about the challenges the hollow body guitars presented in controlling tone and feedback. A tinkerer since the 1920s, Les Paul worked on a concept for a solid body guitar, resulting in the “Log.” Other musicians ridiculed the look of the instrument until Paul added the “wings” so as to resemble the shapes people were used to. Even so, people like Epiphone’s Epi Stathopoulo were less than impressed at first. Paul Bigsby created one of the early attempts for a solid body for Les Paul in 1944. His innovations were more fleshed out in the Travis-Bigsby guitar he made for country picker Merle Travis, with a cast-aluminum bridge, in 1948.

The next year, Fender came out with a design which bolts the neck to the body rather than the traditional dovetail joint. This made the guitar easier and cheaper to make, customize and repair. A pragmatic instrument, coinciding with the mid-century-modernist movement in design and architecture, for the working class musician. The design came out as the Esquire in 1950, eventually evolving to the Broadcaster, and finally the popular Telecaster in 1951. Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Albert Collins, Muddy Waters, Nathaniel Douglas (Little Richard) and Paul Burlison of the Johnny Burnette Rock ’n’ Roll Trio were early adopters of the Telecaster. The Stratocaster came out in 1954, it’s unique quacky tone from three single coil pickups made popular by the most worshipped of guitar heros, Jimi Hendrix.

Surf guitar legend Dick Dale worked closely with Fender on further innovations in amplification and guitar. He needed a louder amp, and they camp up with the 100-watt Fender Showman with 15-inch JBL loudspeakers. “When I plugged that speaker into the Showman amp,” Dale later recalled, “the world of pansy-ass electronics came to an end. It was like Einstein splitting the atom.” The Jazzmaster (1958) and the flashy chrome-surfaced Jaguar (1962) also became popular with surf guitarists. Less expensive student models were introduced, including the Musicmaster and Duo-Sonic (1956) and Mustang (1964), which also became popular with punk musicians in the 70s and 80s. Johnny Ramone used a different guitar, named after surf legends, the Mosrite Ventures II. Ironically it was punk/new wave era artists like Elvis Costello and Television’s Tom Verlaine who helped pull the Jazzmaster out of obscurity.

Another influential partnership between manufacturer and musician was Gretsch and Chet Atkins, who was influenced by Merle Travis, Les Paul and George Barnes. The first Atkins signature guitar was the garish 6120 (1955), featuring a campfire orange finish, kitschy G logo, and engravings of cowboy motifs on the fretboard like steer head, cactus and such. Atkins hated the look but reluctantly used it, and it was a success, outselling Gibson’s concurrent ES-175. Elvis Presley’s guitarist Scotty Moore, Buddy Holly, Cliff Gallup (Gene Vincent) and Eddie Cochran played it. Gretsch also came out with the rocket-shaped Jupiter Thunderbird for Bo Diddley.

Gibson wasn’t to be left behind in the solid-body market, coming up with their version of the solid-body Stradivarius, the Les Paul in 1952. The goldtop version sold for $210, about $20 more than the Telecaster. While Les Paul was at a peak in 1952 with his Galloping Guitars EP, his stardom was soon to fade as a new country-blues hybrd, rockabilly and rock ‘n’ roll became the next big thing. Gibson kept innovating, adding the Tune-o-matic bridge to the Les Paul Custom by 1954, and humbucker pickups designed by Seth Lover in 1955 were added by 1957. The result was a warm, dark, bass-heavy sound of that would differentiate Les Pauls from the brighter Fender sound. They marketed the Les Paul Standard (1958) to jazz players, wrongly assuming the rock ‘n’ roll fad was going away. They had no idea of course, that hard rock and heavy metal were around the corner. They had stopped production in 1961, they same year they introduced a more Modernist looking Les Paul SG, which Les Paul reluctantly posed with in the catalog, but they soon removed his name from it. But later in the 60s, Keith Richards, Eric Clapton, Mike Bloomfield, Peter Green, Jeff Beck, Paul Kossoff, Carlos Santana and Jimmy Page helped revive the Les Paul, prompting them to resume production in 1968. While Tony Iommi most often used an SG (both Gibson and Epiphone have made Iommi signature SGs), he also had a couple Les Pauls, which became a popular axe with the legions of doom bands that sprung up in the 80s and beyond, including Victor Griffin (Pentagram), Scott “Wino” Weinrich (The Obsessed, Saint Vitus, Spirit Caravan), Bruce Franklin (Trouble), and Mats Björkman (Candlemass).

In 1958 Gibson also introduced the ES-335 archtop semi-hollowbody, and a trio of ultra-Modernist designs, the Flying V, the Explorer and the Moderne. However, the Moderne was not put into production until 1982, while the other Modernist designs did not gain much popularity until the metal era. In 1963 they took another shot at a new design that might connect with the current audience, with the Firebird, reflecting hot rod car designs like the Ford Thunderbird, just like Fender did in 1962 with the Jaguar. In 1963 Rickenbacker’s semi-hollow body 12-string 360/12 would soon to be a big hit thanks to an endorsement from the Beatles, cementing it as the guitar of choice for its jangle sound. Also out in 1963 was the teardrop-shaped Vox Mark III which was favored by the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones.

When the garage band explosion happened in the mid-60s, many other less expensive brands became available in department stores rather than specialty music shops, such as Teisco Del Reys, Kents, Silvertones, Ekos, and Hagstroms. With distortion and fuzz becoming more ubiquitous in 1966, the fuzzbox became an important part of the arsenal, starting with Gibson’s Maestro FZ-1 in 1962. There weren’t a lot of options at first, so Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page both used custom made ones by Roger Mayer. Beck also used an early Sola Sound Tone Bender.

Meanwhile, more powerful amps were also required, and eventually produced by Jim Marshall, thanks to collaborations with Pete Townshend. His dad Cliff played sax in big bands with Marshall back in the day. The JTM45 with its separate head, was specifically made to handle distortion. The innovations ultimately lead to the popular Super Lead model 1959, nicknamed the “plexi.” Marshall-style brands Hiwatt and Orange also served the market for heavy fuzz.

An explosion of guitar manufacturers of affordable guitars came out of Italy in the mid-sixties with Eko, Crucianelli, Avanti, Wandre, Goya, Polverini, Meazzi and Gemelli among others. When Leo Fender, ailing with health issues, sold his company to CBS in 1965, quality control eventually suffered as the large conglomerate cut corners. This opened up the market for many other companies to step in during the 70s, including Japanese brands like Tokai, Fernandes, Burny, Univox, and Aria, all more affordable and fairly well made, though Yamaha, ESP and Ibanez were considered a notch better. In 1987 Ibanez partnered with metal maestro Steve Vai and made the monkey-gripped GEM in Loch Ness Green, Flamingo Pink, and Desert Yellow, with pink and green pyramid inlays on the fretboard, and a rainbow of other part colors.

American companies like Peavey, Music Man, Heritage, and B.C. Rich also became established. B.C. Rich joined in on the fun in the 80s with their Warlock series, even more garish and outrageous than the GEM, and embraced by Blackie Lawless of W.A.S.P., Mick Mars of Mötley Crüe, and Slayer’s Kerry King. Ned Steinberger went in the opposite direction with his minimalist, headless guitars and basses, which were especially favored by post-punk artists like Joy Division, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Gang of Four, and Talking Heads.

Some rock stars continued to play an active role in customizing their guitars like Eddie Van Halen with his famous Frankenstrat, which combined his favorite elements of his Les Paul Standard, his ES-335, and his Strat. A copy is displayed in the Smithsonian’s Natural Museum of American History. It’s surprising that it took until past the mid-80s for more bespoke options, like Paul Reed Smith guitars, which can cost several thousand dollars. EGC (Electrical Guitar Company) founded by machinist/luthier Kevin Burkett in Florida in 2004, interestingly services mainly indie post-punk/noise rock and underground stoner/doom/sludge metal musicians like Steve Albini (Shellac), Duane Denison (Jesus Lizard), King Buzzo (Melvins), Scott Kelly (Neurosis), Brent Hinds and Bill Kelliher (Mastodon). The necks, bodies and pickups are usually all aluminum, inspired by Travis Bean Guitars, (Bean, who died in 2011, started in 1974, and in the late 90s, teamed with master machinist/designer B. Kelly Condon to produce 24 highly desirable custom guitars) which can result in some gloriously harsh sounds that befit these genres. However, prices start at $2,900.

Meanwhile, signature guitars continue to be made, often at prices significantly higher than comparable guitars. One cooler recent example is Annie Clark’s (stage name St. Vincent) collaboration with Ernie Ball Music Man, a design that references synth art pop artist Klaus Nomi, 80s Italian Memphis design, 70s Japanese Teiscos and classic car colors, along with a lighter weight and narrower waist to allow for “a boob or two.” Nevertheless, prices range from $1,900 to $2,900.

Not everyone could afford those prices, and garage rocker Jack White of the White Stripes favored, among other gear (Harmony, Kay), a Valco Airline, made for Montgomery Ward in 1964, which originally retailed for under $100. Interestingly, Valco was launched way back in 1942 by Victor Smith, Al Frost, and Louis Dopyera, with roots in the National and Rickenbacker in the 30s. While the Airline is referred to as plastic, it’s actually Res-O-Glas, a state-of-the-art design principle also used on the molded fiberglass bodies of mid-modernist designs of the Chevrolet Corvette and Studebaker Avanti.

However, by the 2000s, thrift-shop vintage guitars weren’t necessarily cost effective, as their old parts tend to chronically fail and need servicing and replacement. The fact that the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach needs to employ a full-time guitar tech to refurbish his arsenal of Silvertone, Harmony, Kay, Teisco and Supro vintage guitars is loaded with irony. It simply became yet another expensive indulgence for those who can afford to collect these artifacts. An admittedly fun hobby for those who want to connect with history, there are better options for beginning guitarists on a budget. The Airline has been revived by Canadian company Eastwood, and its guitars are played by Colin Newman of Wire, Parker Griggs of Radio Moscow and even Steve Vai.

There are now literally thousands of choices of well made guitars that are available new for under $400. For example, Epiphone, which was founded way back in 1873, was the main rival of Gibson in regards to archtops, until 1957, when Gibson’s parent company CMI purchased Epiphone. Since then it gradually offered a less expensive line of Gibson’s products, but still very well made. Sometimes they were so well made they cut into Gibson’s sales, like the Epiphone Del Rey modeled after the Gibson Les Paul double cut. Their Special series of Les Pauls and SGs range between $149 and $199, and are also available in Player Packs that include everything a beginner needs to start — amp, tuner, strap, picks, case, and online guitar lessons, starting at under $200. Imagine how many more people would have taken up electric guitar if something like this was available in 1936 at just under $11, when the Gibson ES-150 was sold for $150 (over $2,743 today).

Squier serves a similar function in relation to Fender guitars, with versions of the Stratocaster, Telecaster, Mustang starting at $130. Squier even has signature guitars, including the Jim Root Telecaster ($400) and the J. Mascis Jazzmaster with an orange creamsicle finish for $450. While Fender and Gibson remain more desirable among most established musicians, Gustav Ejstes (Dungen) and Josh Homme (Queens of the Stone Age) have been seen with an Epiphone ES-335 Dot, while Dave Wyndorf of Monster Magnet used an Epiphone SG. Beatles Lennon and Harrison both had an Epiphone Casino (as well as members of U2, The Strokes and Yeah Yeah Yeahs). Fred Sonic Smith of MC5 used an Epiphone Crestwood Custom, which he sold to Deniz Tek of Radio Birdman.

Yeah, I went a little crazy with Equipboard.com, a community that tracks well-known musicians’ guitar rigs via interviews and eye witness accounts. I grew up playing trumpet, and wished I’d gotten a guitar instead, but figured by the time I was grown up, it was too late. I messed around with guitars owned by various roommates who were in bands through college, bought an acoustic and took lessons at the Old Time School of Folk Music in the 90s, but figured an electric guitar and the accompanying gear would be too expensive to be worth it if I just wanted to just dick around without the intention of playing in a band. As Gary Marcus’ book Guitar Zero shows, it’s never too late to learn, although it definitely can be more difficult with an adult balancing work and family life. But with gear more affordable than ever, it’s no longer cost prohibitive to try out an electric guitar rig.

While I gave a nutshell outline of some of what Play It Loud covers, I highly recommend reading it for the full story. | Buy Play It Loud here

During the course of reading Play It Loud, I researched guitars that I liked simply based on looks (like the Chapman ML1 Norseman Midgardsormen Svart, a bit pricey at $999), and the musicians who use them (the Fender Jaguar was favored by one of my post-punk/garage noir favorites, Rowland S. Howard of The Birthday Party, along with James Williamson of the Stooges, Kurt Cobain, Nick Zinner, Johnny Marr, Emma Ruth Rundle of Marriages, Gemma Thompson of Savages). Of course, the mighty Gibson Les Paul is used by a long list of my favorite artists. It basically came down between a Squier Jaguar and Epiphone Les Paul Studio, both available new for $400. I handled both along with others at my local Guitar Center, and found a used Epiphone for just $250 online at the L.A. store, with a goth matte black finish. It was destined to be mine, along with a used Orange Crush 35RT combo practice amp, skull strap, picks and a stand, everything for just over $500, (the equivalent would be $72 in 1969, $59 in 1959, $27 in 1939). More serious musicians might scoff at my process, but realistically, I will mostly be using it sitting on the same chair that I write and listen to music in the psychedelic doom lair, starting with the free lessons provided by Orange amps to re-learn the chords I’ve long forgotten. It’s basically another way to better understand and appreciate the music that I’ve been obsessed with my entire life.

Over a week later, everything was ready for pickup. During the days of setting it up, tuning and messing around, I contemplated a name for it. My colleague-in rock, Hermi Flagglenack (who has a Gibson SG named Soulstorm, an Epiphone SG named Lady Nightshade, though he recently learned she is no Lady, so just Nightshade, and Ripple the Washburn acoustic), encouraged the naming. His input into the brainstorming — “An all black guitar that eats light. A creature of the night. A shadow lurker. A mysterious entity possibly born in the void of the ethereal abyss. It has a classic shape. Iconic. Legendary. A solid body. Hour glass curves with a cutaway beak (or maybe a thumb?) on the underside. A shape that demands respect. A certain stature radiates from it. It has presence.With its gothic markings, it brings to mind a more than subtle hint at dark romance. Were this creature a gentleman, I see his flat adorned with candle lit dark wood corridors of intricate and somewhat strange artwork. Large hearths are found in several extravagantly furnished rooms in his giant iron gated stone residence. Perhaps it was different before “it” happened. It could be that he now only wishes to commune with the specters that once filled these halls in human form, leaving him now to dance on the edge of sanity. And the sounds. Deep, powerful thunder. Heavy reverberations dance within its wooden skeleton. Screaming, almost vengeful wails erupt as notes are squeezed out of it’s soul. Sonorous and intimidating, but also capable of delivering compassion and comfort to those in need. Heroic, but grounded. A raging iron fist inside a fitted velvet glove.”

My brainstorm ranged from ridiculously cutesy (GIR, Baron von Fuzzmuff) to ridiculously pompous (Namazu the Earthshaker). It’s an important decision, as I didn’t necessarily want the guitar to be made fun of at guitar pre-school and the playground. On the other hand it maybe shouldn’t be so scary and off-putting that it will frighten off potential guitar friends. Just the right balance of friendly and foreboding doom to command respect and admiration. Bogbeater? Gothmog? Jikininki (Jinky) the human-eating ghost (食人鬼)? A dark force lurks in the DOOMcave, that can be heard but not seen…

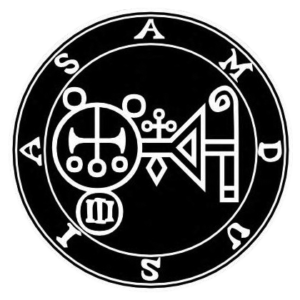

Introducing Amdusias – The Dark Duke.

While Baron Von Fuzzmuff was a popular choice with the test group, dark times calls for a Dark Duke. The 67th demon in the Ars Goetica, an anonymous grimoire on demonology compiled mid-17th century, which is also referenced by Johann Weyer’s Psuedomonarchia Daemonum (1577). The Duke has 29 legions of demons and spirits under his command. He is depicted as a human with claws instead of hands and feet, the head of a unicorn, and a trumpet to symbolize his powerful voice. Amdusias is associated with thunder and it has been said that his voice is heard during storms. In other sources, he is accompanied by the sound of trumpets when he comes and will give concerts if commanded, but while all his types of musical instruments can be heard they cannot be seen.

While Baron Von Fuzzmuff was a popular choice with the test group, dark times calls for a Dark Duke. The 67th demon in the Ars Goetica, an anonymous grimoire on demonology compiled mid-17th century, which is also referenced by Johann Weyer’s Psuedomonarchia Daemonum (1577). The Duke has 29 legions of demons and spirits under his command. He is depicted as a human with claws instead of hands and feet, the head of a unicorn, and a trumpet to symbolize his powerful voice. Amdusias is associated with thunder and it has been said that his voice is heard during storms. In other sources, he is accompanied by the sound of trumpets when he comes and will give concerts if commanded, but while all his types of musical instruments can be heard they cannot be seen.

Amdusias was delighted by the early 20th century offerings from his minions George Beauchamp, Adolph Rickenbacker, Paul A. Bigsby, Les Paul and Leo Fender — the amplified chaos of electric guitars. He is regarded as being the demon in charge of the cacophonous music that is played in Hell. He can also make trees bend at will and likes long walks around lakes of fire.

The next tempting purchase is an effects pedal/fuzz box. A whole other book could/should be dedicated to them. Small companies like EarthQuaker, Malekko, KHDK, Black Arts, Daredevil and Voodoo Lab certainly seem to have a lot of fun experimenting and coming up with entertaining designs, art and names. Many of these cost more than my guitar, so I decided I would wait until I have some basics learned before going that route. That doesn’t stop me from filling my Guitar Center wishlist and monitor for good used deals. Perhaps a simple Electro-Harmonix Op Amp Big Muff, which retails for $80. However, I like the stories behind brand like Black Arts.

I even came up with a fantasy bespoke box, The Yeti Fluffer: Polyamorous Muff Shifter with Ultra Fuzz Overload.

Start with tones sweet and smooth as buttercream squeezed from a donut, then kick the switch into Ultra Fuzz Overload with a distortion thick and tall as redwood trees, massive enough to fluff the most discerning of yeti or sasquatch. The Yeti Fluffer will happily smoosh fluffy muffs with any carbon-based life form of all genders. It’s truly generous, and we daresay gloriously slutty with its fuzz.

The image is repurposed from an EarthQuaker special edition Avalanche Run made for Guitar Center. The artist, Matt Horak, draws Marvel’s Deadpool. Their Rainbow Machine has a “magic” knob that is interesting. KHDK’s Scuzz Box toggles between fuzz, clean and scuzz, while the Malekko Diabolik has fuzz and squish knobs! So many choices.

So how hard is it to learn guitar as an adult? According to cognitive psychologist Gary Marcus in Guitar Zero: The Science of Becoming Musical at Any Age (2012), incredibly hard. While he debunks the popular theories that there is an innate musical instinct and that people can only learn to master an instrument if they start during childhood, Marcus spends a great deal of time documenting how difficult it is to start the path to truly becoming a musician.

So how hard is it to learn guitar as an adult? According to cognitive psychologist Gary Marcus in Guitar Zero: The Science of Becoming Musical at Any Age (2012), incredibly hard. While he debunks the popular theories that there is an innate musical instinct and that people can only learn to master an instrument if they start during childhood, Marcus spends a great deal of time documenting how difficult it is to start the path to truly becoming a musician.

Case in point, Marcus felt the need to take a six month sabbatical from his job to properly start learning guitar (and research his book). That’s not the only advantage Marcus enjoyed due to his status as an esteemed professor and author. He was invited by a friend to take part in a band camp with some talented kids, took guitar lessons from some of the best teachers on the East coast, and advice from luminaries such as jazz guitarist Pat Metheny and Tom Morello (Rage Against The Machine).

In between relating his own struggles with rhythm and breakthrough successes in his learning, he info-dumps a slew of studies and theories, often conflicting, in a seeming haphazard way, making the book a bit of a slog at times. Some repeatedly flog obvious points (learning an instrument is complicated, involving the coordination of the brain being rewired to recognize melodies and harmonies, mastering time, tempo and rhythm, training the muscle memory of hands and fingers to coordinate chord formations and rhythm), while others are fairly enlightening. Humans have not evolved to be inherently musical. Those skillsets are borrowed from their day jobs with other functions. Each brain area used, the amygdala, the superior temporal gyrus, the planum temporale, evolved long before human beings did and is found in many nonmusical species. People slowly and laboriously tune broad ensembles of neural circuitry over time, through deliberate practice. The circuitry is not pre-existing, even if it appears to be the case with some of the more talented humans who definitely take less time to learn than others.

Musical talent is no different than talent for math, painting or sports. They all demand learning and practice. Regarding teaching methods, Marcus compares the strengths and weaknesses of the Suzuki method, the Émile Jaques-Dalcroze method, adopted by Jamie Andreas, author of The Principles of Correct Practice for Guitar (1998) and her flashcards called Fretboard Vitamins, Edwin E. Gordon’s theories of “audiation” — the process of assimilating and comprehending (not simply rehearsing) music. He also admires Malcolm Gladwell’s ideas, but debunks his 10,000 hours of practice to master anything theory by pointing out that the Beatles only spent about 2,000 hours until they emerged from the dank Cavern Club of Hamberg the finely tuned band that would change rock history.

He also addresses that while there are advantages to being able to read and write musical notation, it’s not essential, since none of the Beatles could, nor Eric Clapton, or even composer Irving Berlin. Improvising is a skill that is often neglected with classically trained musicians, resulting in the common situation where brilliant musicians are unable to compose their own music. Marcus also touches on the idea of deliberately avoiding exposure to and knowledge of music to avoid being overtly influenced. That is an ill-advised approach that will more often than not result in the musician coming up with unoriginal ideas that they don’t realize have already been done. Some of the most acclaimed writers such as Dylan, the Beatles, Springsteen and Elton John (Marcus’ examples) had encyclopedic knowledge of music. I’d love to see this explored more, like a massive survey/test to all kinds of songwriters.

When it’s now so easy to create music that’s perfect using computer software, why bother with the arduous task of learning guitar? There are many studies that suggest it’s simply good for the brain, just like learning a new language. This can be helpful factor for those concerned with the possibility of dementia later in life. It definitely enriches one’s understanding of music, appreciation, and even emotional connection to it. Marcus’s most satisfying reason was the fact that about 18 months after first picking up a guitar, he was able to compose an original song for an ailing beloved uncle, and perform it for him and family a little while before he passed. He was able to connect with loved ones in a way that he never would have been able to had he not undertaken the somewhat arduous journey. Not to mention that once the callouses have formed and the pain recedes and one can play actual songs, it’s fun.

A bit less poignant at the end was Marcus’ enthusiasm for a Moog Guitar he bought. Yes, it’s lovely when music can help us in spiritual quests or communicate with loved ones. But often what gets us through the dreary day to day grind, for girls and boys, is our toys. I wonder what kinda pedals he’s accumulated since 2012? | Buy Guitar Zero here

March 29, 2024

Fester’s Lucky 13: 1994

January 4, 2024

Fester’s Lucky 13: 1989

December 1, 2023

Fester’s Lucky 13: 2023 Year-End Summary