Columbia House’s recent bankruptcy filing triggered all kinds of stories, ranging from fond reminiscing about early experiences with record clubs, to surprised reactions that they even still exist as a corporate entity, and a whole slew of whining about how they were killed by streaming services.

Their filing says that Netflix, Amazon, Spotify and Apple crowded it out of the market, preventing Columbia House from getting licensing agreements when it tried to offer streaming services for videos and movies last year. Yes, the more established competitors had an advantage over the new kid on the block. The young, clueless Columbia House, which has been in business since 1955.

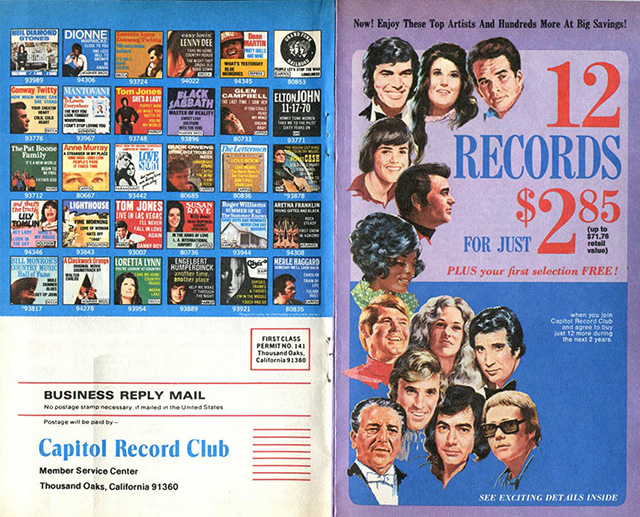

Columbia House pioneered the record club business model, getting millions of consumers on board with the then still new 12″ vinyl LP format, introduced in 1949. Their first year they had 125,175 members who had purchased 700,000 records (for $1.174 million net). By the next year, they had 687,652 members and had sold 7 million records ($14.888 million net), and by 1963, it commanded 10% of the recorded music retail market. By the mid-1960s, they had competition from other clubs, including EMI, Capitol and RCA. At that point, Columbia House was able to stay several steps ahead of the competition when the father of direct marketing, Les Wunderman took over the account. Along with direct marketing, Wunderman introduced innovations such as the database, the 1-800 number, the magazine subscription card, and the credit-card customer rewards program. For Columbia House he created the 12-albums for a penny postage-paid insert card, the Gold Box buried treasure Easter eggs that people could find in the advertising and redeem for free albums, in what he called “interactive” sales in a 1967 speech at M.I.T., decades before the Internet took off. It’s too bad they didn’t keep Wunderman on at least as a consultant to advise them. He’s still around, they should give him a call.

From the 60s through the late 90s, generations of music lovers kickstarted their collections with the ubiquitous introductory offers, buying 3, 6, and eventually 12 albums (ranging in formats from 12″ vinyl, reel-to-reel tapes, 8-track tapes, cassettes and eventually CDs) for a penny, with a certain number to buy after to fulfill the agreement. In the meantime, people had a learning curve as they were introduced to “negative option billing” which meant that they had to mail in a post card to indicate they did not want the selection of the month in order to not receive it. To some, this seemed like a scam, but it was essentially a subscription service. Do nothing and have music chosen for you, or indicate an alternative until you agreement is fulfilled. This model actually existed since 1926, when Maxwell Sackheim and Harry Scherman developed the concept for the Book of the Month Club.

I did this for the first time when I was probably about 11 years old. I didn’t have much money but I had already calculated from what other friends have done that even with all the padded postage and handling charges, I could still end up averaging less than $6.00 an album, which still saved me money. Others must have agreed that they felt they got their value, as Columbia House grew and grew, bringing in a peak revenue of $1.6 billion or $1.83 billion (depending on who you ask) by 1996. RCA set up shop in nearby Indianapolis, became the BMG Record Club by the mid-80s, and offered even better deals, with fewer “free” albums in the introductory offer, but with the commitment to only buy one more at full price. The goal was to keep customers longer by offering more sales, mostly in the form of buy 1, get 2-3 free. I would take advantage of a couple of those, at this point getting cassettes instead of LPs, fulfill my agreement and quit. I’d eventually get invited to join again and do it all over again, this time averaging less than $3.50 a tape.

How could they possibly make money from that model? Well, for one thing, for every person like me, or those who took even more advantage by scamming, having multiple accounts under different nom de plumes, saying they moved out of the country before fulfilling the agreements, there were those who did let the selections of the month pile in, and paid for them full price. Some liked the convenience, others were lazy and just didn’t bother with the cards or returning unwanted items. The other factor was that the headquarters were based in Terre Haute, Indiana, a train hub and manufacturing base where they manufactured the albums themselves, cutting costs on packaging and distrobution. They also used unethical business practices of underpaying the licensing fees. Having such a monopoly on that market segment for so long, other labels couldn’t complain or they’d have their artists dropped from the roster. That is an unfortunate aspect of the music business that is certainly nothing new. Greed and corruption had plagued the business from the beginning, ripping off artists, particularly but not exclusive to black artists, and perhaps their struggles the past 15 years is simply karma.

So yes, bad karma, but also arrogance and stupidity. The 90s saw tons of boomers buying CDs of albums they have already bought at least once, possibly multiple times in various formats, and rebuilding their collections. Combined with the biggest markup in retail history, the result was unprecedented profits to the point where most label executives could roll naked in mountains of cocaine if they wished to. Of course that couldn’t last. Who could expect that to continue? Perhaps only the executive brains addled by too much coke? Filmmaker Chris Wilcha captured what it was like working at Columbia House during this boom time in a low-key, first-person documentary called The Target Shoots First.

The world changes, and the most competitive companies manage to stay in step with the times, if not ahead. As soon as the MP3 digital audio coding format was developed, back in 1991, someone should have anticipated what was coming. Had the companies used some of their big bucks for paying attention to technology and the future. The compressed codec existed in 1991, and was published in 1993. But even if no one could anticipate the perfect storm of small, compressed audio files and quickly increasing available bandwidth on the internet, there was no excuse for their reaction once it happened.

When Napster emerged in 1999, I figured the industry already had a new platform in development to respond to this new market and hold on to their valuable customers. Instead, they sued the fuck out of their customers. The next several years saw the music industry engaged in a frenzied and fruitless game of whack-a-mole, shutting down peer-to-peer networks, prosecuting kids and moms for downloading one top 40 album. But they did very little to actually offer the people who did want to continue buying music, any real value. Essentially their brilliant idea was to offer individual tracks for no less than a dollar each, with little or no discount for quantity, or albums. People who were used to sales and enticing introductory subscription offers, now were seemingly being punished for, at the time what was a relatively small number of people pirating music. It’s not as if that wasn’t always a part of the music business. Bootleg recordings goes back several decades. Taping live performances, from the radio and duplicating albums and sharing among friends was firmly entrenched in music culture. There was a laughable “Home Taping Is Killing Music” ad campaign that most everyone ignored, because the industry was clearly on an upswing. When I was young, I was discovering new music at a really quick pace, but my income was non-existent. In addition to record clubs, and the occasional $5.99 cassette sale at Target, I made do by taping what I could find from the radio, from friends, and once I had a college radio show, from the music library. But for every dollar the music industry considered “lost” or “stolen” during those years were more than made up by the thousands of albums I bought the following years once I did have a job.

When Napster emerged in 1999, I figured the industry already had a new platform in development to respond to this new market and hold on to their valuable customers. Instead, they sued the fuck out of their customers. The next several years saw the music industry engaged in a frenzied and fruitless game of whack-a-mole, shutting down peer-to-peer networks, prosecuting kids and moms for downloading one top 40 album. But they did very little to actually offer the people who did want to continue buying music, any real value. Essentially their brilliant idea was to offer individual tracks for no less than a dollar each, with little or no discount for quantity, or albums. People who were used to sales and enticing introductory subscription offers, now were seemingly being punished for, at the time what was a relatively small number of people pirating music. It’s not as if that wasn’t always a part of the music business. Bootleg recordings goes back several decades. Taping live performances, from the radio and duplicating albums and sharing among friends was firmly entrenched in music culture. There was a laughable “Home Taping Is Killing Music” ad campaign that most everyone ignored, because the industry was clearly on an upswing. When I was young, I was discovering new music at a really quick pace, but my income was non-existent. In addition to record clubs, and the occasional $5.99 cassette sale at Target, I made do by taping what I could find from the radio, from friends, and once I had a college radio show, from the music library. But for every dollar the music industry considered “lost” or “stolen” during those years were more than made up by the thousands of albums I bought the following years once I did have a job.

By 2000, it seemed like a no-brainer. The music clubs, no stranger to offering new and different formats, could simply offer digital files in addition to the others. There’s many ways to go about it, and they had the resources to do it. To be fair, the prices should reflect the fact that they do not have to manufacture and distribute physical product. Yes, that would undercut the popularity of the CDs, but that was happening anyway. I could easily imagine a Netflix-like subscription would have done extremely well. $15/month for 3 digital albums a month (all the common formats, including lossless), $25 for 6, $35 for 10 and so on. Subscribers could select genres like they used to do for Columbia/BMG for recommended new releases (new releases available at midnight on actual release date). Those prices should at least comparable to the record club days that would balance out free offers with inflated “handling” charges. Imagine the boost in music sales if more people start buying multiple albums a month again, just considering it another cost of entertainment like cable or Netflix. This kind of service would ideally not be limited to labels. Unsigned bands like those on Bandcamp should be included too. If only the record industry had done this a decade ago, instead of running around playing whack-a-mole litigation. And of course taking part in a lot of unnecessary and whining.

Marketing music was probably too easy for a long time, as there was a built-in audience that obsessively sought out music with very little effort from the industry since the 60s. At the end of the 90s, sure, the sudden widespread availability of digital files changed things a bit, but all consumers really wanted was to not feel ripped off. And to expect people to go from paying on average $15 a CD to $1 a song (with many albums containing more than 15 songs), but not physical product or artwork, then of course they’re going to feel ripped off. Additionally, when there is a downward shift in demand, usually that causes prices to drop. Despite a class action suit for price fixing which had the labels paying a $143 million settlement to customers who purchased CDs between Jan. 1, 1995, and Dec. 22, 2000, nothing really changed. They still stubbornly refused to drop CD prices, and downloads were still priced high throughout the 2000s and 2010s, and not presented in a way that’s convenient for mainstream consumers not dedicated enough to hunt down a Bandcamp page.

What’s crazy is that amidst all the panic and the whining Columbia House was still pulling in over $1 billion a year from 2001 to 2003. But rather than invest their massive resources into properly marketing digital music, they did nothing but waste a bunch on needless overhead and take part in a series of useless corporate mergers starting with the 2002 acquisition by Blackstone Group. As the music industry floundered, attacked, sued and prosecuted their customers, and continually dropped the ball in making even the most simple efforts at selling digital albums, streaming services gradually picked up the slack. Interfaces were clunky, sound quality was bad and available selections were minimal at first, but gradually, services such as Last.fm, Pandora and Rhapsody picked up steam. In 2008, a Swedish start-up started Spotify, and managed to get licensing for more artists and albums available for on-demand streaming than the others. By September 2010, they had 10 million users, but was not yet able to negotiate a deal with the labels for the U.S. market. It finally launched in the U.S. on July 14, 2011, and by December 2012 it had 20 million users and 5 million paid subscribers, and by June 2015, 75 million users and 20 million paid subscribers.

As expected, there’s a lot of complaining about the amount of royalties Spotify is paying to artists. In a better world, Spotify would be integrated with a sophisticated model that draws customers in to buy music from favorite artists by offering incentives such as concert tickets, fan clubs, t-shirts, special edition CDs/digital albums with bonus tracks, subscriptions, etc. Oops, no one bothered to do that. Who’s fault is that? It seems streaming fills a role that’s somewhat in between FM radio (which pays a similarly small amount of royalties, but only to the songwriters, a system that’s just as flawed and contentious as anything), and cable TV. Except that there is currently no one who is intelligently marketing to these streaming users to buy anything. According to what I’m reading in social media, blogs and news stories, Spotify seems to be paying out as much as they’re able at this point, considering the fact that they only make so much in advertising with the free accounts, and subscribers pay just $10 a month. With people now used to paying over $100 a month for cable TV, that’s not a lot. I expect in the near future Spotify and other services will start limiting the available content on the free accounts and gradually increase the price of the subscription services. They just better be sure to add value, or they’ll lose all their customers.

In the meantime, there’s been a trend of shaming the customers for using Spotify and not purchasing enough music. That’s just fucking stupid. It’s the industry’s job to offer value and incentive to attract customers. There has never been a successful business model that guilts people into paying more money than they want to or have to. A growing number of mostly successful mega-selling mainstream artists are pulling their albums from Spotify, including Thom Yorke, Taylor Swift, The Black Keys and Björk. It’s certainly their right, and they don’t really need Spotify as a promotional tool, because they already have pretty loyal following. Maybe it’s not a big deal, but some of those loyal fans might have bought quite a few of their CDs, but never did get around to ripping them onto their computers, so they sold the CDs, and subscribed to Spotify in good faith that their favorite artists would not be yanking their albums off the service.

Additionally, some artists are signing exclusive deals to just one streaming service. Eventually in order to access all your favorite artists, you may need to subscribe to multiple streaming services. In the eyes of some that might not be a bad thing, but personally, I spent decades building and curating my collection. When I finally did sell off the majority of my CD collection, I made sure to rip them to FLAC, and keep two backups. I still buy a number of CDs, weeding them out at the end of the year and selling some, and pay for downloads pretty much exclusively through Bandcamp, the only service that consistently offers albums in lossless format at usually reasonable prices. Sometimes I pay for an album twice that I downloaded on Bandcamp, that I like so much I buy the CD, often direct from the band at a show. Occasionally I even pay ridiculously high prices for a CD, like Anekdoten’s Until All The Ghosts Are Gone. The idea that I still have to occasionally pay import prices for an album kind of pisses me off. This is very much a global market that should not have such price inequities. Nevertheless, there are still some small European labels that do not have their shit together, or simply do not choose to charge reasonable prices for a download. If I like a band enough I’ll make an occasional exception. With any artist or label willing to make their content unavailable at any time, while many other albums just are not available to begin with on streaming services, I believe my collection is still immensely valuable. Storage continues to get cheaper (5TB for $130, woo hoo!), and eventually, hopefully, SDXC chips will fulfill the promise of 2TB chips, and I will be able to carry my collection in my pocket in a tiny DAP (digital audio player). I will never be at the mercy of the whims of artists, labels or streaming services.

My latest batch of CDs, pre-orders of new releases from Amazon, and a sale from Stormspell Records.

I don’t know if there will be a major revival of buying music or not. It seems it would still benefit the most serious music fans the most. But there are also people who cannot make buying more music a priority over, say, feeding their kids. And kids and others without jobs and disposable incomes who cannot pay a lot of money for entertainment. They are not the bad guys here. The consumers cannot and should not be blamed for the failings of the music industry. Whether the downward trend of buying music can change depends entirely on whether the music industry can remove their heads from their asses and help make it happen.

By the way, Columbia House did not go out of business. They are still operating, on a limited scale, selling DVDs. The bankruptcy is simply allowing the owners to get out of debt, and sell the company at a competitive price. As of August 10, there were 20 purchasers and investors expressing interest. That could be a mighty powerful brand someone could get just for a song, so to speak. Maybe Netflix should buy it. Whoever does so, I hope they use it wisely and do not waste the opportunity by making it into another half-assed service that offers no real value, and then whine about it.

April 12, 2024

The School of Post-Punk – Class of ’83

March 29, 2024

Fester’s Lucky 13: 1994

February 29, 2024

Best of 1984