Children will always be afraid of the dark, and men

with minds sensitive to hereditary impulses will always tremble at the thought

of the hidden and fathomless worlds of strange life which may pulsate in the

gulfs beyond the stars or press hideously upon our own globe in unholy dimensions

which only the dead and the moonstruck may glimpse.— H.P. Lovecraft, “Supernatural Horror in Literature”

September 21 was the Autumn Equinox, when the equator is in the direct path of the sun, day and night are of equal length, and when the dark commences to become dominant. It’s a time of harvest, when grapes are fermented into wine, and livestock too weak to survive the winter are butchered. Festivals of Mabon, Dionysus, Michaelmas, Wine Harvest, Cornucopia, Feast of Avalon, Rosh Hashanah/Yom Kippur and Alban Elfed are celebrated. Autumn is a time for respite after labor and reflection. It’s a time for letting go of things that had their time and are slipping away. It’s a time for flowers and leaves to wilt, wither, dry and sink into the earth. It’s also a time when recurrent hauntings are most often reported.

During this time, upbeat, sunny music doesn’t feel quite right anymore. Imagine sitting in a pub with your cronies, a substantial beer in your hand, or whiskey, cider, cocoa, even glog. The candles flicker from the draft of a nearby window, rattled by a stiff wind from the dark night, carrying with it the first hint of winter chill. Skeletal tree branches perform eerie shadow puppet shows on the window, giant claws slyly beckoning potential victims to leave the comfort of the pub to be swallowed by the howling wind. At this moment, if someone were to put on a bouncy pop ditty on the jukebox, they would be pinned down by murderous glares. Music should blend with the mood and atmosphere. In this case, something sturdier, and somber is called for. Music that would not interfere with a good, macabre ghost story. Fortunately there has been an abundance of such music in the past few years, including the hellfire and brimstone of Sixteen Horsepower, the resigned despair of Black Heart Procession, the morbid tall tales of The Handsome Family, the frenzied, sinister carnival music of Firewater, the aching expressiveness of The Dirty Three and the majestic sadness of Godspeed You Black Emperor. Death and melancholy are subjects most people in their right minds tend to avoid. Yet in the right time and place, these very words strangely invoke a thrill that can almost be recalled with nostalgia.

During this time, upbeat, sunny music doesn’t feel quite right anymore. Imagine sitting in a pub with your cronies, a substantial beer in your hand, or whiskey, cider, cocoa, even glog. The candles flicker from the draft of a nearby window, rattled by a stiff wind from the dark night, carrying with it the first hint of winter chill. Skeletal tree branches perform eerie shadow puppet shows on the window, giant claws slyly beckoning potential victims to leave the comfort of the pub to be swallowed by the howling wind. At this moment, if someone were to put on a bouncy pop ditty on the jukebox, they would be pinned down by murderous glares. Music should blend with the mood and atmosphere. In this case, something sturdier, and somber is called for. Music that would not interfere with a good, macabre ghost story. Fortunately there has been an abundance of such music in the past few years, including the hellfire and brimstone of Sixteen Horsepower, the resigned despair of Black Heart Procession, the morbid tall tales of The Handsome Family, the frenzied, sinister carnival music of Firewater, the aching expressiveness of The Dirty Three and the majestic sadness of Godspeed You Black Emperor. Death and melancholy are subjects most people in their right minds tend to avoid. Yet in the right time and place, these very words strangely invoke a thrill that can almost be recalled with nostalgia.

What better way to interrogate fear and melancholia than to immerse oneself in music, as the leaves turn color and nights grow longer. So what constitutes autumnal music? For brevity’s purpose, this essay will focus on late 20th and turn-of-the-century popular Western music. Named after the season, music of autumn must be at least somewhat in tune with the vengeful force that is Mother Nature, much like the art and literature of Romanticism. Americana would logically have a strong autumnal bent, with its earthy roots in bluegrass, gospel, folk, blues and country. The extreme emotions of expressionism, Poe, Baudelaire and Lovecraft would also be influential.

In a time when entire subcultures of at least two generations grew up on goth and death metal, it’s hard to imagine not having dark music around. Yet for a long time there was very little of what can be defined as Autumnal music. The culture of fear and melancholy seem to be intrinsically linked, and a constant presence in life. Yet for a good part of the 18th century, it was unfashionable. The 1700s were the Age of Enlightenment. Materialism, rationality and optimism took the place of superstition and pessimism, as science claimed to unshackle people from the chains of the ancient fears of the unknown and supernatural, along with the horror of plagues and uncivilized violence. It’s impressive the amount of faith placed upon science and reason, when for so long it was accepted that it’s a brutal, cruel world. People who lived in the Middle Ages (5th century to 15th century) were much more intimate with death. Death was not something that happened only to elderly people who were safely tucked into rest homes out of sight and out of mind. Few people in the middle ages had the luxury of old age — they were lucky to make it to their 40s. Disease, famine and war routinely kept life spans short. During the black plague, death was the way of life. Music, of course, isn’t the only indicator of an era’s Zeitgeist. This was vividly depicted in the Teutonic cosmos as collected by brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Karl Grimm, in the form of fairy tales dating back to the pre-Christian era. The stories documented a woman who decapitates her stepson, chops up his corpse, and cooks him up in a stew for her husband (“Juniper Tree”), and how Rapunzel’s suitor is blinded when sharp thorns pierce his eyes. They cover kidnappings, beheadings, gruesome murders, cruel and drawn-out punishments, and violent revenges. And these are children’s stories! Folk tales from the Middle Ages would prove influential to many, including American writer Washington Irving, whose The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (1819-1820) contained “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” a story based on a German folk tale about Ichabod Crane’s encounter with a headless horseman.

While sallow Autumn fills thy lap with leaves/Or Winter, yelling thro’ the troublous air…

— William Collins, “Ode to Evening,” (1747)

Fair Science frown’d not on his humble birth/And Melancholy mark’d him for her own.

— Thomas Gray, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (1751)

In 1789, the French Revolution marked the end of the Age of Enlightenment. Especially during the frenzied violent stages in 1792-1794, and later the Napoleonic Wars (1799-1815), the ideals of rationalism seemed naive. Even before that, literature was demonstrating disillusionment and resistance to the norm, as evinced in William Collins’ “Ode to Evening” (1747) and “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (1751) by Thomas Gray. In these poems, they expressed a preference for nature and mysticism over science, emphasizing romantic melancholy and what German writer E. T. A. Hoffmann later described as “infinite longing” — the essence of the Romanticism era. Influenced by the romantic spirit of German folk songs, Gothic architecture and English playwright William Shakespeare, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and his compatriots, philosopher and critic Johann Gottfried von Herder and historian Justus Möser, provided more formal foundations for Romanticism in a group of essays entitled Von deutscher Art und Kunst (Of German Style and Art, 1773). Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) set a tone and mood that would influence the romantics — a tendency to abandon, melancholy, world-weariness and self-destruction.

In 1789, the French Revolution marked the end of the Age of Enlightenment. Especially during the frenzied violent stages in 1792-1794, and later the Napoleonic Wars (1799-1815), the ideals of rationalism seemed naive. Even before that, literature was demonstrating disillusionment and resistance to the norm, as evinced in William Collins’ “Ode to Evening” (1747) and “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (1751) by Thomas Gray. In these poems, they expressed a preference for nature and mysticism over science, emphasizing romantic melancholy and what German writer E. T. A. Hoffmann later described as “infinite longing” — the essence of the Romanticism era. Influenced by the romantic spirit of German folk songs, Gothic architecture and English playwright William Shakespeare, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and his compatriots, philosopher and critic Johann Gottfried von Herder and historian Justus Möser, provided more formal foundations for Romanticism in a group of essays entitled Von deutscher Art und Kunst (Of German Style and Art, 1773). Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) set a tone and mood that would influence the romantics — a tendency to abandon, melancholy, world-weariness and self-destruction.

Folk ballads from the Middle Ages were often used for inspiration, such as Scottish poet James MacPherson’s Gaelic-influenced volumes in the 1760s. English poet Thomas Percy collected Scottish and English folktales and ballads, culminating in his work, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765). Tales gathered by the Grimm Brothers, Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen and E.T.A. Hoffmann were often set in ghost-haunted ruins and graveyards, with frightening supernatural themes of mystery and horror. Gothic novelist Horace Walpole fused these elements in The Castle of Otranto (1765), influencing many others, including Clara Reeve — The Champion of Virtue (1777); Ann Radcliffe — The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794); Matthew Gregory Lewis — Ambrosio, or the Monk (1796); Charles Robert Maturin — The Fatal Revenge (1807); Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley — Frankenstein (1818); and Charles Brockden Brown, the first American professional novelist. English poet John Keats distilled the gothic themes in “The Eve of St. Agnes,” along with summarizing the emotional tone of Romanticism in “Ode on Melancholy” (1820). Influenced by German mystic Jakob Boehme, William Blake pioneered a unique form of illustrated verse. Blake’s friend, the Swiss-English painter Henry Fuseli, exemplified what British writer and statesman Edmund Burke identified as vastness, obscurity, and a capacity to inspire terror. Paintings such as The Nightmare (1781), with its horrific apparition of a gnome/devil and a horse’s head with glowing eyes and The Night-Hag Visiting the Lapland Witches (1796) emphasized melodrama, fantasy and horror, much like the etchings of monsters and demons by the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya’s, such as Old Man Straying Among Phantoms (1815-24) and particularly his Black Paintings, including the disturbing Saturn Devouring One of his Sons (1820-23). French painter Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819) was the first truly epic Romantic example of agony in the most gruesome detail.

Folk ballads from the Middle Ages were often used for inspiration, such as Scottish poet James MacPherson’s Gaelic-influenced volumes in the 1760s. English poet Thomas Percy collected Scottish and English folktales and ballads, culminating in his work, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765). Tales gathered by the Grimm Brothers, Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen and E.T.A. Hoffmann were often set in ghost-haunted ruins and graveyards, with frightening supernatural themes of mystery and horror. Gothic novelist Horace Walpole fused these elements in The Castle of Otranto (1765), influencing many others, including Clara Reeve — The Champion of Virtue (1777); Ann Radcliffe — The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794); Matthew Gregory Lewis — Ambrosio, or the Monk (1796); Charles Robert Maturin — The Fatal Revenge (1807); Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley — Frankenstein (1818); and Charles Brockden Brown, the first American professional novelist. English poet John Keats distilled the gothic themes in “The Eve of St. Agnes,” along with summarizing the emotional tone of Romanticism in “Ode on Melancholy” (1820). Influenced by German mystic Jakob Boehme, William Blake pioneered a unique form of illustrated verse. Blake’s friend, the Swiss-English painter Henry Fuseli, exemplified what British writer and statesman Edmund Burke identified as vastness, obscurity, and a capacity to inspire terror. Paintings such as The Nightmare (1781), with its horrific apparition of a gnome/devil and a horse’s head with glowing eyes and The Night-Hag Visiting the Lapland Witches (1796) emphasized melodrama, fantasy and horror, much like the etchings of monsters and demons by the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya’s, such as Old Man Straying Among Phantoms (1815-24) and particularly his Black Paintings, including the disturbing Saturn Devouring One of his Sons (1820-23). French painter Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819) was the first truly epic Romantic example of agony in the most gruesome detail.

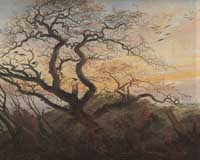

Awesomely moody landscapes like Monastery Graveyard in the Snow (1817-19) and The Tree of Crows (1822), by German painter Caspar David Friedrich epitomize not only melancholy and isolation, but the powerless human awe and fear of the ominous forces of nature. French classical music composer (Louis) Hector Berlioz was one of the few of the Romantic era to create music that so vividly mirrored the visual artists of their time. Symphonie Fantastique (1831), particularly the “Witche’s Sabbath” and “March to the Scaffold” movements featured tolling bells and trombones playing the notes to the wildly ghoulish medieval chant, “dies irae.” Also important was Camille Saint-Saëns, who successfully evoked the haunting loneliness in the vastness of nature of Friedrich’s paintings with Danse Macabre (1874), a symphonic tone poem that about the medieval symbolic representation of death, possibly influenced by the 14th century epidemics of bubonic plague. Folklore portrays the dance performed by skeletons in the graveyard.

Awesomely moody landscapes like Monastery Graveyard in the Snow (1817-19) and The Tree of Crows (1822), by German painter Caspar David Friedrich epitomize not only melancholy and isolation, but the powerless human awe and fear of the ominous forces of nature. French classical music composer (Louis) Hector Berlioz was one of the few of the Romantic era to create music that so vividly mirrored the visual artists of their time. Symphonie Fantastique (1831), particularly the “Witche’s Sabbath” and “March to the Scaffold” movements featured tolling bells and trombones playing the notes to the wildly ghoulish medieval chant, “dies irae.” Also important was Camille Saint-Saëns, who successfully evoked the haunting loneliness in the vastness of nature of Friedrich’s paintings with Danse Macabre (1874), a symphonic tone poem that about the medieval symbolic representation of death, possibly influenced by the 14th century epidemics of bubonic plague. Folklore portrays the dance performed by skeletons in the graveyard.

Romanticism could not, however, hold back science and progress. A year after William Wordsworth’s long poem “The Prelude” (1850), which speaks of “… the close and overcrowded haunts/Of cities, where the human heart is sick,” the first world’s fair opened in 1851 at the Crystal Palace in London. It introduced technological innovations and in turn, the Industrial Revolution. Science once again was in control, for better or worse. The worst being the horror story by Scottish novelist Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Rather than some mystical unknown horror, Dr. Jekyll is transformed into a monster as a result of simple laboratory chemicals. Even Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) could be hunted down and destroyed by scientist Van Helsing. Yet the spirit of Romanticism did not disappear entirely. In poems like “Lenore” (1831) and “The Raven” (1845), American writer Edgar Allan Poe romanticized death and dread, elevating misery into a place of refuge, a grand and beautiful thing. He became the first master of the short-story form, with inventively grotesque stories like “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1839) and “The Cask of Amontillado” (1846). Poe became an influence of Symbolists, especially French poet Charles Pierre Baudelaire, who became known for his translations of Poe’s work. Baudelaire’s volume of poetry, The Flowers of Evil (1857) was inspired by Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination. Exulting in the beauty of the malignant, it emphasizes the mystery and tragedy of human existence. It was filled with imagery of black cats, tortured demons and phantoms. Such imagery was brought to life by Belgian symbolist painter James Ensor, who portrayed humanity as grotesque clowns and

Romanticism could not, however, hold back science and progress. A year after William Wordsworth’s long poem “The Prelude” (1850), which speaks of “… the close and overcrowded haunts/Of cities, where the human heart is sick,” the first world’s fair opened in 1851 at the Crystal Palace in London. It introduced technological innovations and in turn, the Industrial Revolution. Science once again was in control, for better or worse. The worst being the horror story by Scottish novelist Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Rather than some mystical unknown horror, Dr. Jekyll is transformed into a monster as a result of simple laboratory chemicals. Even Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) could be hunted down and destroyed by scientist Van Helsing. Yet the spirit of Romanticism did not disappear entirely. In poems like “Lenore” (1831) and “The Raven” (1845), American writer Edgar Allan Poe romanticized death and dread, elevating misery into a place of refuge, a grand and beautiful thing. He became the first master of the short-story form, with inventively grotesque stories like “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1839) and “The Cask of Amontillado” (1846). Poe became an influence of Symbolists, especially French poet Charles Pierre Baudelaire, who became known for his translations of Poe’s work. Baudelaire’s volume of poetry, The Flowers of Evil (1857) was inspired by Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination. Exulting in the beauty of the malignant, it emphasizes the mystery and tragedy of human existence. It was filled with imagery of black cats, tortured demons and phantoms. Such imagery was brought to life by Belgian symbolist painter James Ensor, who portrayed humanity as grotesque clowns and  skeletons in paintings such as Skeletons Trying to Warm Themselves (1889) portraying skeletons’ futile efforts to try to regain the light of life. Masks and Death (1897), shows a skull surrounded by masks, with demons overhead. Artist Decomposed shows his fascination with death. Triumph of Death (1896) shows skeletons and demons with scythes wreaking havoc on Brussels. Norwegian painter Edvard Munch’s The Cry (or The Scream, 1893) typified the anguished expression of isolation and fear that would influence the development of German expressionism, with its themes of death and misery as shown through the lens of the subjective emotional inner life.

skeletons in paintings such as Skeletons Trying to Warm Themselves (1889) portraying skeletons’ futile efforts to try to regain the light of life. Masks and Death (1897), shows a skull surrounded by masks, with demons overhead. Artist Decomposed shows his fascination with death. Triumph of Death (1896) shows skeletons and demons with scythes wreaking havoc on Brussels. Norwegian painter Edvard Munch’s The Cry (or The Scream, 1893) typified the anguished expression of isolation and fear that would influence the development of German expressionism, with its themes of death and misery as shown through the lens of the subjective emotional inner life.

Aside from the exceptions of a few symbolists the demise of Romanticism in the late 19th century seemed to indicate that there was little demand for grim, melancholy art. The respite from fear and horror was relatively short-lived, however, as World War I reacquainted the Western world with catastrophic deaths of millions, bringing death back into daily life (most of the rest of the world did not enjoy the luxury of a respite from genocide, starvation, war and hardship). Rationality was put aside for the need to deal with death, comforting themselves with renewed interest in spiritualism and psychic investigation. Austrian-Czech writer Franz Kafka pre-figured late 20th century despair and anxiety with nightmarish tales of waking up as an enormous insect in “The Metamorphosis” (1915), which was an interesting juxtaposition to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which had been an inspiration for so many works of art during the Romantic period. Kafka was also influenced by German expressionism, which gave voice to War-induced anxieties, inner terrors, and cynicism. German films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) employed masklike makeup and grim backdrops to evoke expressionism’s nightmarish imagery. The music of Arnold Schoenberg and Alan Berg of Austria, Paul Hindesmith of Germany, Béla Bartók of Hungary and Sergey Prokofiev of Russia abandoned “pretty” harmonies for more dissonant harmonies and atonal, distorted melodies.

New Englander H.P. Lovecraft evolved his craft from being derivative of Poe, to nearly surpassing his inspiration with depictions of epic dread in short stories like “The Call of Cthulhu” (1926) and “The Dunwich Horror” (1928). Still, few took note, and the horror fare of thirties’ movies, King Kong, Count Dracula and Frankenstein enjoyed only cult popularity. The majority of the audiences were eating up light escapist fare like screwball comedies. World War II, however, truly brought reality home. In two nuclear blasts, science turned from savior to bogeyman, creating biological and nuclear weapons capable of apocalyptic destruction. Confronted with the fragility of life on the entire planet, everything was questioned, and it took more than movie monsters to inspire fear. Mad scientists, prehistoric beasts and creatures form outer space tried to either take over the world or destroy it. Modern art now regularly dealt with fear and horror. William Faulkner, who wrote 20 novels between 1929 and 1962 that told epic tales of biblical conflict and redemption, created the southern gothic novel. (Mary) Flannery O’Connor added Wise Blood (1952) and The Violent Bear It Away (1960) and several short stories. Author and illustrator Edward Gorey pioneered a particularly morbid brand of black humor, exemplified by “The Gashleycrumb Tinies” (1963).

By the end of the 1960s, depletion of natural resources, religious warfare, governmental and industrial corruption, political assassination, street crime, mass murder and drug addiction made people jaded to the point that only pure biblical evil could frighten. Hence, the Devil reared its head in movies Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973) and The Omen (1976). From then on, horror became a way of life for a generation that barely blinks an eye at Satanic worship or extreme violence. It’s a generation that grew up on dozens of horror movies, along with punk, goth and death metal, a far cry from the optimistic hippie music of the 60s. It’s a generation that voraciously consumed horror novels by Anne Rice and Stephen King, and fell in love with Tim Burton’s Edward Gorey-meets-Disney movies depicting macabre flights of fancy. While it has a smaller audience, Burton’s Goreyesque book, The Melancholy Death of Oyster Boy and Other Stories was also influential of a small subculture of comic artists who made death and misery . . . strangely cute. Roman Dirge’s Lenore, tells stories about a cute little dead girl. Something at the Window is Scratching: Children’s Tales for Disturbed Children would probably have been met with howls of protest were it published 40, even 20 years ago. Jhonen Vasquez push the boundaries of taste and sanity with the disturbing blacker-than-coal humor of Johnny The Homicidal Maniac and Squee. Vasquez and Dirge have even collaborated on a children’s cartoon called Invader Zim aired on Nickelodian. In a sense, we have come full circle. For the first time since the Middle Ages, the world is so filled with horrors that children’s exposure to gruesome, macabre stories are no big deal, because reality offers even worse monsters to fear. Such is the therapeutic benefits of embracing grim reapers and haunted melancholy — to make reality all that much easier to deal with.

In pop music, one of the first interrogations of fear and dread occured in 1967, with The Doors’ Oedipal epic “The End,” which dealt with shockingly murderous and grim subject matter for the time. The ominous dirge was very influential for years to come. Aside from Jim Morrison’s Dionysian decadence and poetic pretensions, the rest of their music, aside from the gloomy “Riders On The Storm” feels Autumnal. While goth, inspired by The Doors, Bauhaus and Joy Division, and death metal, inspired by Black Sabbath and Venom, certainly qualify as dark music, they are too overtly cartoonish, artificial and overbearing to qualify. While a band like Joy Division certainly doesn’t lack depth or emotional honesty, it seems to communicate a distinctly urban experience, with their pre-industrial angst.

Van Morrison’s more subdued melancholy made a stronger case as autumnal music, particularly with Astral Weeks (1968), a series of stream-of-consciousness songs written after his lover died of tuberculosis. Having abandoned his band, his record label hired musicians trained in jazz and classical to accompany Morrison in the studio. He gave them little direction on what to play, other than giving them lyrics and vague suggestions of a key or two. The music miraculously gelled, often in the first take. The musicians later recounted how something magic seemed to occur, as if a ghost guided their efforts. Particularly haunting was the mystical seven-minute “Astral Weeks.” The rustic folk-rock of Fairport Convention taps into the timeless melancholy of European folk tradition, especially on the apocalyptic nine-minute “A Sailor’s Life.” British folk compatriot Nick Drake broke boundaries in soul-crushing isolation and gloom with haiku-like simplicity in songs like “Three Hours,” “Fly” and the harrowing, apocalyptic “Black Eyed Dog” and “Voice From the Mountain.” On John Wesley Harding (1968), Bob Dylan touches on a rural country vibe to tell startlingly biblical visions of mythology and dread in “All Along the Watchtower,” “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” and “The Wicked Messenger.” Blood On the Tracks (1975) finds Dylan reeling from the traumatic breakup of a marriage. Songs like “Tangled Up In Blue,” “Shelter From the Storm,” and “Buckets of Rain” transcend normal breakup songs with allegories and vivid imagery of coldness, wind, rain and blood that make it quintessential music for autumn. Neil Young also took folk into new directions on his second solo album, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (1969), featuring expressionist guitar epics “Cowgirl In The Sand” and “Down By The River,” a strangled murder ballad. Time Fades Away (1973), On The Beach (1974) and Tonight’s The Night (1975) are a funereal trilogy of harrowing, drunken songs of despair, as Young felt surrounded by death.

After a brief dearth of autumnal music, Captain Beefheart picked up the ball on his last album, Ice Cream For Crow (1982). The music is particularly sparse and brittle, sounding like a walk through a dried forest. Beefheart’s nature imagery reaches a natural conclusion, with references to bones and skeletons, concluding his career in music. At the same time, R.E.M. began their career by creating a unique style that blended Fairport Convention and the Byrds with more post-punk influences. The initial result on Murmur (1983) was a murky sound with cryptic, mumbled vocals creating a bucolic whole. Produced by Joe Boyd (Fairport Convention), Fables of the Reconstruction (1985) is an eerie psychedelic-folk classic, with creatively disorientating, sinister sonic textures and cryptic lyrics that tell creepy rural Southern legends. Another band steeped in folk legends is The Pogues. On Red Roses for Me (1984), they combine Irish folk ballads with drunken punk energy in songs like “Transmetropolitan,” “Streams of Whiskey”, and “Down in the Ground Where the Dead Men Go.” They further tightened their craft with the Elvis Costello-produced Rum, Sodomy & the Lash (1985) and If I Should Fall From The Grace Of God (1987).

Eleventh Dream Day combined the expressive guitars of Neil Young’s second album with the likes of Television’s “Marquee Moon” (1977) and Dream Syndicate’s “When You Smile” (1982). The result was Prairie School Freakout (1987), a raw document of brittle, brooding elegies, such as “Among The Pines” (“a cold fall rain/a distant vague pain/a long black train/shoo and sway/through soggy New England forests/a chosen place of farewells”) and “Tarantula” (“blood pours from concrete thoughts/life was getting hard”). “Tenth Leaving Train” starts with a painful goodbye, then blasts off from the stratosphere in mournful guitar heaven. Like-minded Chicago band Red Red Meat evoke a similar mood, with somewhat more fragmentary rhythms in “Bury Me,” “Buttered” and “Carpet Of Horses.” Califone, a spin-off band lead by Tim Rutilli, emphasizes an even murkier, rustic sound on Roomsound (2001).

Come on along with the Black Rider

We’ll have a gay old time

Lay down in the web of the black spider

I’ll drink your blood like wine

So come on in

It ain’t no sin

Take off your skin

And dance around your bones

— Tom Waits, “The Black Rider”

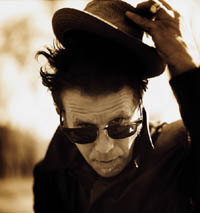

Tom Waits had a long career as a barroom troubadour, singing lyrics influenced by Beat poetry, minstrel music and Hoagy Carmichael. By the early 80s he collaborated with his new wife, playwright Kathleen Brennan, and seemed to discover Captain Beefheart on Swordfishtrombones (1983) and Rain Dogs (1985). On Franks Wild Years (1987), he shows signs of transcending his influences with the poetic “Blow Wind Blow” and “Cold Cold Ground,” which manages to evoke a powerful autumnal nostalgia with plenty of surrealistic imagery. Bone Machine (1992) is Waits at his undeniable peak. Ripe with morbid imagery, the album is his most consistent statement — truly a definitive document of autumnal music. As the title suggests, the sounds suggest sinister rattling bones and scorched earth, not unlike Beefheart’s Ice Cream For Crow. The albums starts with full-blown apocalypse with “The Earth Died Screaming,” with the menacing clacking sound of an army of skeletons. The bleak resignation of “Dirt In The Ground” contemplates death in every earthy, wormy detail. “Black Wings,” a song about either a mass murderer or the grim reaper, summarizes the mood of the album — “When the moon is a cold chiseled dagger/Sharp enough to draw blood from a stone/He rides through your dreams on a coach/And horses and the fence posts/In the moonlight look like bones.” Waits was on a role, and the next year he collaborated on an operetta with William S. Burroughs and Robert Wilson, called The Black Rider (1993). Those unfortunate enough to miss the live production that only appeared in New York and Germany, were consoled with Wait’s versions of the music originally written to be performed by the cast. The Black Rider tells the tale of a circus carny named George Schmid who is challenged to a duel to the death over a woman, and sells his soul to the devil for a set of magic bullets in order to ensure his victory. Much of the music is even more evocative and spooky that Bone Machine. In “The Black Rider,” a ghoulish barker invites you into the big top where he’ll “drink your blood like wine” and “use your skull for a bowl.” Practically an ode to autumn, “November” sets the mood — “November/It only believes/In a pile of dead leaves/And a moon/That’s the color of bone.” “Just The Right Bullets” is sung from the perspective of the devil, in an appropriately frightening voice. “Crossroads” finds George negotiating with the devil. The music is perfectly executed in its rustic glory by a chamber band, complete with a theramin or bowed saw that invokes spells and apparitions of dancing ghosts. “Oily Night” recalls the nightmarish imagery of Henry Fuseli, lending the claustrophobic feeling of being buried in a pigpile of goblins and trolls.

Tom Waits had a long career as a barroom troubadour, singing lyrics influenced by Beat poetry, minstrel music and Hoagy Carmichael. By the early 80s he collaborated with his new wife, playwright Kathleen Brennan, and seemed to discover Captain Beefheart on Swordfishtrombones (1983) and Rain Dogs (1985). On Franks Wild Years (1987), he shows signs of transcending his influences with the poetic “Blow Wind Blow” and “Cold Cold Ground,” which manages to evoke a powerful autumnal nostalgia with plenty of surrealistic imagery. Bone Machine (1992) is Waits at his undeniable peak. Ripe with morbid imagery, the album is his most consistent statement — truly a definitive document of autumnal music. As the title suggests, the sounds suggest sinister rattling bones and scorched earth, not unlike Beefheart’s Ice Cream For Crow. The albums starts with full-blown apocalypse with “The Earth Died Screaming,” with the menacing clacking sound of an army of skeletons. The bleak resignation of “Dirt In The Ground” contemplates death in every earthy, wormy detail. “Black Wings,” a song about either a mass murderer or the grim reaper, summarizes the mood of the album — “When the moon is a cold chiseled dagger/Sharp enough to draw blood from a stone/He rides through your dreams on a coach/And horses and the fence posts/In the moonlight look like bones.” Waits was on a role, and the next year he collaborated on an operetta with William S. Burroughs and Robert Wilson, called The Black Rider (1993). Those unfortunate enough to miss the live production that only appeared in New York and Germany, were consoled with Wait’s versions of the music originally written to be performed by the cast. The Black Rider tells the tale of a circus carny named George Schmid who is challenged to a duel to the death over a woman, and sells his soul to the devil for a set of magic bullets in order to ensure his victory. Much of the music is even more evocative and spooky that Bone Machine. In “The Black Rider,” a ghoulish barker invites you into the big top where he’ll “drink your blood like wine” and “use your skull for a bowl.” Practically an ode to autumn, “November” sets the mood — “November/It only believes/In a pile of dead leaves/And a moon/That’s the color of bone.” “Just The Right Bullets” is sung from the perspective of the devil, in an appropriately frightening voice. “Crossroads” finds George negotiating with the devil. The music is perfectly executed in its rustic glory by a chamber band, complete with a theramin or bowed saw that invokes spells and apparitions of dancing ghosts. “Oily Night” recalls the nightmarish imagery of Henry Fuseli, lending the claustrophobic feeling of being buried in a pigpile of goblins and trolls.

Nick Cave took roots of folk tradition, gothic horror and biblical imagery to original peaks that proved highly influential. Born in Australia, Nick Cave moved to London with his first band, The Birthday Party, to be closer to the intense post-punk scene, focusing on intensely chaotic, dissonant, grim music like Public Image Ltd., Gang Of Four, Magazine, Joy Division, The Pop Group and Einstürzende Neubauten. By the last two EPs The Birthday Party had slowed from a spastically powerful extension of Iggy Pop & The Stooges to a menacing, deliberate crawl, on songs like “Deep In The Woods” and “Jennifer’s Veil.” Cave broke up the band in order to emphasize storytelling over chaos. The result was The Bad Seeds, a post-punk supergroup made up of members of Magazine and Neubauten. From 1984 to 1988, Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds released four passionately brooding albums of Old Testament terror and rustic southern gothic intrigue. Cave even published a novel heavily influenced by Flannery O’Connor and William Faulkner called And The Ass Saw The Angel (1988). On The Firstborn Is Dead, (1985) he continued his obsession with the American rural south by interrogating the blues – trains, floods, imprisonment, sin and death. “The Carny” is an sordid tale of a circus gone horribly wrong, and was featured in German director Wim Wenders’ classic portrayal of epic longing, Wings Of Desire (1988). “The Mercy Seat” is Cave’s most powerful song, written from the viewpoint of a man about to be executed. Later, Cave seemed to have satisfied his dark side and turned to Brazilian pop, Leonard Cohen-influenced love ballads and New Testament optimism. He flipped to the dark side for old time’s sake on Murder Ballads (1996). There were plenty of artists willing to reap the dark seeds sown by Cave, most notably PJ Harvey. To Bring You My Love (1995) features the title track, which finds Harvey quoting Bo Diddley and cursing God in a frightening statement of purpose, backed by a low-tuned guitar and foreboding organ. The songs on that album and Is This Desire? (1998) are full of religious metaphors that borrow equally from the blues, Captain Beefheart, Cave and Tom Waits. “Angelene,” “The Wind,” “Catherine,” “The Garden” and “The River” describe fictional characters evoking stark nature imagery.

Nick Cave took roots of folk tradition, gothic horror and biblical imagery to original peaks that proved highly influential. Born in Australia, Nick Cave moved to London with his first band, The Birthday Party, to be closer to the intense post-punk scene, focusing on intensely chaotic, dissonant, grim music like Public Image Ltd., Gang Of Four, Magazine, Joy Division, The Pop Group and Einstürzende Neubauten. By the last two EPs The Birthday Party had slowed from a spastically powerful extension of Iggy Pop & The Stooges to a menacing, deliberate crawl, on songs like “Deep In The Woods” and “Jennifer’s Veil.” Cave broke up the band in order to emphasize storytelling over chaos. The result was The Bad Seeds, a post-punk supergroup made up of members of Magazine and Neubauten. From 1984 to 1988, Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds released four passionately brooding albums of Old Testament terror and rustic southern gothic intrigue. Cave even published a novel heavily influenced by Flannery O’Connor and William Faulkner called And The Ass Saw The Angel (1988). On The Firstborn Is Dead, (1985) he continued his obsession with the American rural south by interrogating the blues – trains, floods, imprisonment, sin and death. “The Carny” is an sordid tale of a circus gone horribly wrong, and was featured in German director Wim Wenders’ classic portrayal of epic longing, Wings Of Desire (1988). “The Mercy Seat” is Cave’s most powerful song, written from the viewpoint of a man about to be executed. Later, Cave seemed to have satisfied his dark side and turned to Brazilian pop, Leonard Cohen-influenced love ballads and New Testament optimism. He flipped to the dark side for old time’s sake on Murder Ballads (1996). There were plenty of artists willing to reap the dark seeds sown by Cave, most notably PJ Harvey. To Bring You My Love (1995) features the title track, which finds Harvey quoting Bo Diddley and cursing God in a frightening statement of purpose, backed by a low-tuned guitar and foreboding organ. The songs on that album and Is This Desire? (1998) are full of religious metaphors that borrow equally from the blues, Captain Beefheart, Cave and Tom Waits. “Angelene,” “The Wind,” “Catherine,” “The Garden” and “The River” describe fictional characters evoking stark nature imagery.

Firewater is a relatively raucous combination of Nick Cave, Tom Waits and the Pogues. Lead by Tod A., formerly of Cop Shoot Cop, the band blends in carnival music, klezmer, Latin and sea shantys on songs like “The Circus,” “El Borracho” and “7th Avenue Static.” Former Screaming Trees vocalist Mark Lanegan and Colorado’s Sixteen Horsepower also carry on the darkness as Cave acolytes. Lanegan focuses on grim, folky tales about the common everyman, best exemplified on Field Songs (2001), while the accordion-driven Sixteen Horsepower focus on more ominously melodramatic hellfire and brimstone, with a sharp intensity on songs like “Burning Bush” and “Splinters” that recall the power of Joy Division more than a folk band. Black Heart Procession combines all the above influences with added elements like piano-led European influences of French balladeer Jacques Brel. Musical saws,

Firewater is a relatively raucous combination of Nick Cave, Tom Waits and the Pogues. Lead by Tod A., formerly of Cop Shoot Cop, the band blends in carnival music, klezmer, Latin and sea shantys on songs like “The Circus,” “El Borracho” and “7th Avenue Static.” Former Screaming Trees vocalist Mark Lanegan and Colorado’s Sixteen Horsepower also carry on the darkness as Cave acolytes. Lanegan focuses on grim, folky tales about the common everyman, best exemplified on Field Songs (2001), while the accordion-driven Sixteen Horsepower focus on more ominously melodramatic hellfire and brimstone, with a sharp intensity on songs like “Burning Bush” and “Splinters” that recall the power of Joy Division more than a folk band. Black Heart Procession combines all the above influences with added elements like piano-led European influences of French balladeer Jacques Brel. Musical saws,  eerie bells and accordions add a chilling theatrical cabaret feel to 1 (1998) and 2 (1999) and 3 (2000), particularly on “The Waiter,” “The Old Kind of Summer,” “A Light So Dim,” “We Always Knew,” “Once Said At the Fires” and “I Know Your Ways.” In “The Winter My Heart Froze,” the piano-organ instrumental suggests nothing less than the return of Nosferatu. Were The Afghan Whigs commissioned to score a heart-wrenchingly bleak theater production, it might sound something like The Black Heart Procession, and quintessentially autumnal. Thalia Zedek, whose roots (NYC noise bands Uzi and Live Skull) lie within the same clanging background as Cave’s The Birthday Party, Einsturzende Neubauten, The Swans and Sonic Youth, recently released Been Here & Gone (2001) that perfectly synthesizes the strengths of Cave, Waits, The Dirty Three, Sixteen Horsepower and The Black Heart Procession. The aformentioned bands have also produced fairly worthy additions to the autumnal cannon, including Sonic Youth’s <i>Bad Moon Rising</i> (1985), Einsturzende Neubauten’s <i>Tabula Rasa</i> and The Swans’ <i>The Great Annihilator.</i>

eerie bells and accordions add a chilling theatrical cabaret feel to 1 (1998) and 2 (1999) and 3 (2000), particularly on “The Waiter,” “The Old Kind of Summer,” “A Light So Dim,” “We Always Knew,” “Once Said At the Fires” and “I Know Your Ways.” In “The Winter My Heart Froze,” the piano-organ instrumental suggests nothing less than the return of Nosferatu. Were The Afghan Whigs commissioned to score a heart-wrenchingly bleak theater production, it might sound something like The Black Heart Procession, and quintessentially autumnal. Thalia Zedek, whose roots (NYC noise bands Uzi and Live Skull) lie within the same clanging background as Cave’s The Birthday Party, Einsturzende Neubauten, The Swans and Sonic Youth, recently released Been Here & Gone (2001) that perfectly synthesizes the strengths of Cave, Waits, The Dirty Three, Sixteen Horsepower and The Black Heart Procession. The aformentioned bands have also produced fairly worthy additions to the autumnal cannon, including Sonic Youth’s <i>Bad Moon Rising</i> (1985), Einsturzende Neubauten’s <i>Tabula Rasa</i> and The Swans’ <i>The Great Annihilator.</i>

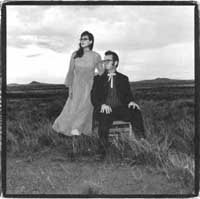

Will Oldham, who goes by the names Palace Brothers, Palace Music, Palace Songs, Palace and Bonnie Prince Billy, was first known for his role in John Sayles’ Matewan. Oldham attacks Appalachian folk in a similar way Nick Cave borrowed from the blues, with the same evangelical fervor of biblical imagery. Songs like “Werner’s Last Blues,” “Come In,” “Stable Will” and “Trudy Dies” are sparsely acoustic, but with heavy doses of strife and black humor. Similarly, tongue is at least slightly placed in cheek with The Handsome Family in their Carter Family-influenced Appalachian mountain folk that is so deranged that it’s almost ridiculous. However, they pull off the spooky tales of despair with aplomb on murder ballads “Up Falling Rock Hill,” “My Beautiful Bride” and “Poor, Poor Lenore,” a tribute to the hapless heroine in Edgar Allan Poe’s poem. Chicago-based Pinetop Seven adds mandolin, slide guitar, accordion, toy piano and upright bass to the rich Americana feel on Rigging The Toplights (1998), thanks largely to the instrumental talents of Charles Kim. Darren Richard narrates the stories of loss and desolation in “The Fear of Being Found” and “Empty Hands And the Long Walk Home.” Calexico offers a cinematic twist in their instrumentals in the form of Mexican mariachis with marimbas and vibraphones. The result is hybrid of Mexican, country, western and folk with occasionally sublime moments of sadness.

Will Oldham, who goes by the names Palace Brothers, Palace Music, Palace Songs, Palace and Bonnie Prince Billy, was first known for his role in John Sayles’ Matewan. Oldham attacks Appalachian folk in a similar way Nick Cave borrowed from the blues, with the same evangelical fervor of biblical imagery. Songs like “Werner’s Last Blues,” “Come In,” “Stable Will” and “Trudy Dies” are sparsely acoustic, but with heavy doses of strife and black humor. Similarly, tongue is at least slightly placed in cheek with The Handsome Family in their Carter Family-influenced Appalachian mountain folk that is so deranged that it’s almost ridiculous. However, they pull off the spooky tales of despair with aplomb on murder ballads “Up Falling Rock Hill,” “My Beautiful Bride” and “Poor, Poor Lenore,” a tribute to the hapless heroine in Edgar Allan Poe’s poem. Chicago-based Pinetop Seven adds mandolin, slide guitar, accordion, toy piano and upright bass to the rich Americana feel on Rigging The Toplights (1998), thanks largely to the instrumental talents of Charles Kim. Darren Richard narrates the stories of loss and desolation in “The Fear of Being Found” and “Empty Hands And the Long Walk Home.” Calexico offers a cinematic twist in their instrumentals in the form of Mexican mariachis with marimbas and vibraphones. The result is hybrid of Mexican, country, western and folk with occasionally sublime moments of sadness.

The Welsh Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci tap into the rural-folk energy of Fairport Convention with their airily bucolic psychedelia. Particularly on How I Long To Feel That Summer In My Heart (2001), they epitomize autumnal nostalgia. Adding a further European feel to the Americana-heavy autumnal music, Pram’s Museum of Imaginary Animals (2000) is hallucinatory, like a child’s nightmare about Fellini-esque carnies, that would not be out of place on a soundtrack to The City Of Lost Children (1995). On Sparklehorse’s latest, It’s A Wonderful Life (2001), Mark Linkous is blessed by autumnal druids Tom Waits and PJ Harvey on an album that exemplifies rustic beauty and fantastical imagery of “the toothless kiss of skeletons” to “circus people with hairy little hands.”

The Dirty Three are an Australian-based instrumental trio who sound like Ennio Morricone scoring a modern tragedy that takes place in lonesome deserts, dark forests and great plains torn to bits by tornados. They are the aural equivalent to German painter Caspar David Friedrich’s desolate and frightening landscapes. It’s no wonder that Nick Cave now employs them as part-time Bad Seeds. “Everything’s Fucked,” “The Last Night” and “Hope” portrays human angst on the scale of hurricanes. Every strength is displayed on the heart wrenching, 14 minute “I Offered It Up To The Stars & The Night Sky.” With Warren Ellis’ passionate violin and Mick Turner’s suggestive guitar and Jim White’s broad stroked drums, the music tells stories without words better than most bands can with lyrics. Cat Power comes close, probably because on Moon Pix (1998) she’s backed by two-thirds of The Dirty Three. On “Say,” one can literally hear the ominous thunder in the great expanse of the Australian outback. The cover of “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” takes away the chorus and strips it down to the bare melancholic essence. Canadian nine-piece Godspeed You Black Emperor! is a groundbreaking instrumental group that manages to summon the forces of nature into its dramatic, nearly heroic music, while pushing forward with experimentalism and found-sound collage. They will potentially be one of the most influential bands in the next couple years, in turn redefining the parameters of autumnal music.

The Dirty Three are an Australian-based instrumental trio who sound like Ennio Morricone scoring a modern tragedy that takes place in lonesome deserts, dark forests and great plains torn to bits by tornados. They are the aural equivalent to German painter Caspar David Friedrich’s desolate and frightening landscapes. It’s no wonder that Nick Cave now employs them as part-time Bad Seeds. “Everything’s Fucked,” “The Last Night” and “Hope” portrays human angst on the scale of hurricanes. Every strength is displayed on the heart wrenching, 14 minute “I Offered It Up To The Stars & The Night Sky.” With Warren Ellis’ passionate violin and Mick Turner’s suggestive guitar and Jim White’s broad stroked drums, the music tells stories without words better than most bands can with lyrics. Cat Power comes close, probably because on Moon Pix (1998) she’s backed by two-thirds of The Dirty Three. On “Say,” one can literally hear the ominous thunder in the great expanse of the Australian outback. The cover of “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” takes away the chorus and strips it down to the bare melancholic essence. Canadian nine-piece Godspeed You Black Emperor! is a groundbreaking instrumental group that manages to summon the forces of nature into its dramatic, nearly heroic music, while pushing forward with experimentalism and found-sound collage. They will potentially be one of the most influential bands in the next couple years, in turn redefining the parameters of autumnal music.

With real-life horrors looming increasingly close to home, there is a need now more than ever to acknowledge our fears and confront our sadness. Autumnal music offers a comforting opportunity to cry in your beer, commiserate with a loved one, nostalgically recall childhood celebrations of Halloween and The Day of the Dead, or allow yourself, for a moment, to be scared witless. Frankly, anyone who can’t appreciate at least one type of autumnal music should be suspected of suffering from a certain lack of character depth. At the risk of burning eternally in Hell, I would say that aside from the brutal reality of war, every person enjoys being frightened at times. Because no one feels quite so alive as when they have looked into the glowing red eyes of the Grim Reaper and lived to tell about it.

With real-life horrors looming increasingly close to home, there is a need now more than ever to acknowledge our fears and confront our sadness. Autumnal music offers a comforting opportunity to cry in your beer, commiserate with a loved one, nostalgically recall childhood celebrations of Halloween and The Day of the Dead, or allow yourself, for a moment, to be scared witless. Frankly, anyone who can’t appreciate at least one type of autumnal music should be suspected of suffering from a certain lack of character depth. At the risk of burning eternally in Hell, I would say that aside from the brutal reality of war, every person enjoys being frightened at times. Because no one feels quite so alive as when they have looked into the glowing red eyes of the Grim Reaper and lived to tell about it.

Music for Autumn: A Discography

Songs that are particularly excellent examples are listed underneath. Some are linked to the Fast ‘n’ Bulbous reviews. Certain albums stand as a cohesive statement, and no tracks are singled out. Since these albums were categorized as such due only to perceived mood, it’s highly subjective. If there are any albums you believe should be added to the list, feel free to let me know.

- Beck * Sea Change (Interscope) 02

- The Black Heart Procession * 1 (Cargo) 98(“The Waiter,” “The Old Kind of Summer,” “Release My Heart,” “Blue Water-Black

Heart,” “The Winter My Heart Froze,” “Stitched To My Heart,”

“Square Heart”) - The Black Heart Procession * 2 (Touch & Go) 99(“The Waiter #2,” “Blue Tears,” “A Light So Dim,” “The Waiter #3”)

- The Black Heart Procession * Three (Touch & Go) 00(“We Always Knew,” “Once Said At the Fires,” “Waterfront (The Sinking

Road),” “I Know Your Ways,” “Never From This Heart,” “A

Heart Like Mine,” “On Ships of Gold”) - The Black Heart Procession * Amore del Topico (Touch And

Go) 02 - Calexico * The Black Light (Quarterstick) 98(“Gypsy’s Curse,” “The Ride (Pt. II),” “Where Water

Flows,” “Sideshow,” “Chach,” “Over Your Shoulder,”

“Sprawl,” “Old Man Waltz”) - Calexico * Hot Rail (Quarterstick) 00(“Untitled III,” “Untitled II,” “Drenched,”

“Tres Avisos”) - Calexico * Aerocalexico (Our Soil, Our Strength) 01(“Transistorites,” “Clothes Of Sand,”

“Finale Fucked,” “Sequoia,” “Humano,” “Accordian

Waltz”) - Califone * Roomsound (Perishable) 01(“Porno Starlet Vs. Rodeo Clown”)

- Captain Beefheart & the Magic Band * Ice Cream For Crow

(Virgin) 82(“Ice Cream For Crow,” “The Host, the Ghost, the Most Holy-O,” “Cardboard

Cutout Sundown,” “’81’ Poop Hatch,” “The Thousandth and Tenth Day of the Human

Totem Pole,” “Skeleton Makes Good.”) - Neko Case * Blacklisted (Bloodshot)

02(“Things That Scare Me,” “Deep Red Bells,” “Look

For Me (I’ll Be Around),” “Pretty Girls,” “Blacklisted,”

“Ghost Wiring”) - Cat Power * Moon Pix (Matador) 98(“American Flag,” “Say”)

- Cat Power * The Covers Record (Matador)

00(“(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”) - Nick Cave & The Birthday Party * The Bad Seed/Mutiny! (4AD)

83(“Deep In The Woods,” “Wildworld,” “Jennifer’s Veil”) - Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds * From Her To Eternity (Homestead)

84(“From Her To Eternity,” “The Moon Is In The Gutter,” “A Box For Black Paul”) - Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds * The Firstborn Is Dead (Homestead)

85(“Say Goodbye To the Little Girl Tree,” “Train Long-Suffering”) - Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds * Your Funeral . . . My Trial

(Homestead) 86(“Stranger Than Kindness,” “Jacks Shadow,” “The Carny,” “She Fell Away”) - Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds * Tender Prey (Mute) 88(“The Mercy Seat,” “Up Jumped The Devil,” “Sunday’s Slave,”

“Sugar Sugar Sugar”) - Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds * The Good Son (Mute) 90(“Sorrow’s Child,” “The Weeping Song,” “The Hammer

Song,” “Lament”) - Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds * Henry’s Dream (Mute) 92(“Papa Won’t Leave You, Henry,” “Christina The Astonishing,”

“John Finn’s Wife,” “Loom of the Land”) - Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds * Let Love In (Mute) 94(“Do You Love Me?,” “Loverman,” “Red Right Hand,”

“Ain’t Gonna Rain Anymore”) - Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds * Murder Ballads (Mute) 96(“Song Of Joy,” “Stagger Lee,” “The Curse Of Millhaven,” “Crow Jane”)

- Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds * The Boatman’s Call (Mute)

97(“Where Do We Go Now But Nowhere?,” “West Country Girl”) - Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds * No More Shall We Part (Reprise)

01(“As I Sat Sadly By Her Side,” “Fifteen Feet Of Pure White

Snow”) - Dirty Three (Touch & Go) 95(“Better Go Home Now,” “Odd Couple,” “Kim’s Dirt,”

“Everything’s Fucked,” “The Last Night”) - The Dirty Three * Horse Stories (Touch & Go) 96(“1000 Miles,” “Sue’s Last Ride,” “Hope,” “I Remember A Time When

Once You Used To Love Me,” “At The Bar” ) - The Dirty Three * Ocean Songs (Touch

& Go) 98 - The Dirty Three * Whatever You

Love You Are (Touch & Go) 00(“I Offered It Up To The Stars & The Night Sky,” “Some Things I Just Don’t

Want To Know,” “I Really Should’ve Gone Out Last Night”) - Dr. John * Gris-Gris (Collectors) 68(“Gris-Gris Gumbo Ya Ya,” “Danse Kalinda Boom,” “Danse

Fambeaux,” “I Walk On Guilded Splinters”) - Dr. John * Babylon (Wounded Bird) 69(“Glowin’,” “Black Widow Spider,” “The Lonesome Guitar

Strangler”) - Dr. John * Remedies (Wounded Bird) 70

- (“Loop Garoo,” “Angola Anthem”)

- Dr. John * The Sun, Moon & Herbs (Wounded Bird) 71(“Black John the Conquerer,” “Pots on Fiyo

(File Gumbo),” “Zu Zu Mamou”) - Nick Drake * Five Leaves Left (Island) 68(“Three Hours”)

- Nick Drake * Bryter Layter (Island) 70(“Fly”)

- Nick Drake * Pink Moon (Island) 72(“Pink Moon,” “Horn,” “Know,” “Parasite,”

“Harvest Breed”) - Nick Drake * Time Of No Reply 68-74 (Rykodisc)( “Black Eyed Dog,” “Voice From the Mountain”)

- Bob Dylan * John Wesley Harding (Columbia) 68(“All Along the Watchtower,” “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine,” “The Wicked

Messenger”) - Bob Dylan * Blood On The Tracks (Columbia) 75(“Tangled Up In Blue,” “If You See Her, Say Hello,” “Shelter From the Storm,”

and “Buckets of Rain”) - Einsturzende Neubauten * Tabula Rasa (Mute) 93(“Wüste”)

- Eleventh Dream Day * Prairie School Freakout (Amoeba) 87(“Among the Pines,” “Tarantula,” “Tenth Leaving Train”)

- Eleventh Dream Day * Lived To Tell (Atlantic) 91(“It’s Not My World,” “North Of Wasteland”)

- Eleventh Dream Day * Ursa Major (Atavistic) 94(“Orange Moon”)

- Eleventh Dream Day * Eighth (Thrill Jockey) 97(“Two Smart Cookies,” “Last Call”)

- Eleventh Dream Day * Stalled Parade (Thrill Jockey) 00(“Stalled Parade”)

- Fairport Convention * What We Did on Our Holidays (Hannibal)

69 - Fairport Convention * Unhalfbricking (Hannibal) 69(“A Sailor’s Life”)

- Fairport Convention * Liege and Lief (A&M) 69(“Farewell Farewell,” “Matty Groves,” “Reynardine,” “Tam-Lin”)

- Fairport Convention * Full House (Hannibal) 70(“Flowers of the Forest,” “Sloth”)

- Firewater * Get Off The Cross, We Need the Wood For the

Fire (Jetset) 96(“The Circus”) - Firewater * The Ponzi Scheme (Jetset) 98(“El Borracho,” “Drunkard’s Lament”)

- Firewater * Psychopharmacology (Jetset) 01(“7th Avenue Static,” “The Man With The Blurry Face”)

- Godspeed You Black Emperor! * f#a# (Kranky) 98

- Godspeed You Black Emperor! * Slow Riot For New Zero Kanada

EP (Kranky) 99 - Godspeed You Black Emperor! *

Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas To Heaven (Kranky) 00 - Godspeed You Black Emperor! * Yanqui U.X.O. (Constellation)

02 - Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci * Spanish Dance Troupe (Mantra/Beggars

Banquet) 99(“Faraway Eyes,” “Murder Ballad”) - Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci * The Blue Trees (Mantra) 00(“Foot And Mouth ’68”)

- Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci * How I

Long To Feel That Summer In My Heart (Mantra/Beggars Banquet) 00(“These Winds Are In My Heart,” “Christina”) - The Handsome Family * Through The Trees (Carrot Top) 98(“Weightless Again,” “My Sister’s Tiny Hands,” “Bury

Me Here,” “My Ghost”) - The Handsome Family * In The

Air (Carrot Top) 00(“Poor, Poor Lenore,” “Up Falling Rock Hill,” “My Beautiful Bride,” “When

That Helicopter Comes”) - Handsome Family * Twilight

(Carrot Top) 01(“Cold, Cold, Cold,” “A Dark Eye,” “The White Dog”) - PJ Harvey * To Bring You My Love (Island) 95(“To Bring You My Love,” “C’mon Billy,” “Long Snake Moan,” “Send His Love

To Me,” “The Dancer” [& B-Sides] “Somebody’s Down, Somebody’s Name,” “Darling

Be There”) - PJ Harvey * Is This Desire? (Island)

98( “Angelene,” “The Wind,” “Catherine,” “The Garden,” “The River”) - Horse Stories * Travelling Mercies (For Troubled Paths)

(Loose UK) 02 - Mark Lanegan * The Winding Sheet (Sub Pop) 89(“Mockingbirds,” “Undertow,” “Eyes Of A Child,”

“The Winding Sheet”) - Mark Lanegan * Whiskey For the Holy Ghost (Sub Pop) 93(“Kingdoms Of Rain,” “Carnival,” “Riding The Nightingale,”

“Dead On You”) - Mark Lanegan * Scraps At Midnight (Sub Pop) 98(“Bell Black Ocean,” “Waiting On A Train,” “Praying

Ground”) - Mark Lanegan * I’ll Take Care Of You (Sub Pop) 99(“Carry Home,” “Creeping Coastline Of Lights”)

- Mark Lanegan * Field Songs (Sub Pop)

01(“Miracle,” “Resurrection Song,” “Blues For D,”

“Fix”) - Eleni Mandell * Snakebite

(Spacebaby) 02(“Dreamboat,” “Pirate Song,” “Dutch Harbor”) - Van Morrison * Astral Weeks (WB) 68(“Astral Weeks”)

- Van Morrison * Veeden Fleece (WB) 74

- Nina Nastasia * The Blackened

Air (Touch and Go) 02(“I Go With Him,” “Oh, My Stars,” “In

The Graveyard,” “Ocean”) - The Palace Brothers * There Is No One What Will Take Care

Of You (Drag City) 93(“You Will Miss Me When I Burn,” “Come A Little Dog”) - Palace Brothers (Drag City) 94

- Palace Songs * Hope EP (Drag City) 94(“Werner’s Last Blues To Blokbuster”)

- Palace Music * Viva Last Blues (Drag City) 95

- Palace * Arise Therefore (Drag City) 96

- Palace Music * Lost Blues And Other Songs (Thrill Jockey)

97(“Ohio River Boat Song,” “Rudy Dies,” “Come In,” “Horses,” “Stable Will”) - Palace/Will Oldham * Guarapero: Lost Blues 2 (Drag City)

00(“Drinking Woman”) - Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy * Ease Down The Road (Palace Records)

01 - Papa M * Whatever, Mortal (Drag

City) 01(“Over Jordan,” “Beloved Woman,” “The Lass Of Roch

Royal,” “The Unquiet Grave”) - Picastro * Red Your Blues (Pehr) 01

- Pinetop Seven * Rigging The Toplights (Truckstop/Atavistic)

98(“The Fear of Being Found,” “Empty Hands And the Long Walk Home.” - Pinetop Seven * Bringing Home The Last Great Strike (Truckstop)

00(“As The Mutiny Sleeps,” “The Palm Acres Parade,” “Untitled,”

“November, 4 am,” “Buried In St. Cloud”) - The Pogues * Red Roses For Me (WEA) 84(“Transmetropolitan,” “Streams of Whiskey”, and “Down in the Ground Where

the Dead Men Go”) - The Pogues * Rum Sodomy & The Lash (WEA) 85(“The Sick Bed of Cuchulainn,” “The Old Main Drag,” “Dirty Old Town,” “The

Band Played Waltzing Matilda”) - The Pogues * If I Should Fall From The Grace Of God (WEA)

87(“Fairytale of New York,” “Thousands Are Sailing,” “Streets of Sorrow,” “Lullaby

of London”) - Pram * Helium (Too Pure) 94(“My Father The Clown”)

- Pram * Sargasso Sea (Too Pure) 95(“Cotton Candy”)

- Pram * Music For Your Movies EP (Too Pure) 97

- Pram * North Pole Radio Station (Merge)

98(“Cinnabar,” “El Topo,” “Fallen Snow,” “The

Clockwork Lighthouse”) - Pram * Museum Of Imaginary Animals (Too Pure) 00

- Red Red Meat (Perishable) 93(“Bury Me”)

- Red Red Meat * Bunny Gets Paid (Sub Pop) 95(“Carpet of Horses,” “Buttered”)

- Red Red Meat * There’s A Star Above The Manger Tonight

(Sub Pop) 97 - R.E.M. * Chronic Town EP (IRS) 82

- R.E.M. * Murmur (IRS) 83(“Talk About The Passion,” “Shaking Through”)

- R.E.M. * Fables of the Reconstruction (IRS) 85(“Feeling Gravitys Pull,” “Maps and Legends,” “Driver 8,” “Life And How To

Live It,” “Old Man Kensey”) - Sixteen Horsepower * Sackcloth ‘n’ Ashes (A&M) 95(“I Seen What I Saw,” “Black Soul Choir,” “Scrawled

In Sap,” “Horse Head,” “Harm’s Way,” “American

Wheeze,” “Neck On The New Blade”) - Sixteen Horsepower * Low Estate (A&M) 97(“Low Estate,” “For Heaven’s Sake,” “Pure Clob Road,”

“Phyllis Ruth,” “Golden Rope”) - Sixteen Horsepower * Secret

South (Razor & Tie) 00(“Cinder Alley,” “Burning Bush,” “Silver Saddle,” “Splinters,”

“Just Like Birds,” “Strawfoot”) - Sixteen Horsepower *

Folklore (Jetset) 02(“Hutterite Mile,” “Blessed Persistence,” “Alone and Forsaken,”

“Beyond the Pale,” “Horse Head Fiddle,” “Sinnerman,”

“Flutter”) - Sonic Youth * Bad Moon Rising (Blast First) 85(“I Love Her All The Time,” “Ghost Bitch,” “Death

Valley ’69”) - Sparklehorse * It’s A Wonderful

Life (EMI/Parlophone) 01(“Apple Bed,” “Eyepennies”) - The Swans * The Great Annihilator (Young God) 95

- The Swans * Soundtracks for the Blind (Atavistic) 96

- Tom Waits * Franks Wild Years (Island) 87(“Blow Wind Blow,” “Please Wake Me Up,” “More Than Rain,” “Cold Cold Ground”)

- Tom Waits * Bone Machine (Island) 92(“Earth Died Screaming,” “Dirt in the Ground,” “All Stripped Down,” “Goin’

Out West,” “Murder in the Red Barn,” “Black Wings”) - Tom Waits * The Black Rider (Island) 93(“The Black Rider,” “November,” “Just The Right Bullets,” “Black Box Theme,”

“Flash Pan Hunter,” “Russian Dance,” “Crossroads,” “Oily Night”) - Tom Waits * Mule Variations (Epitaph)

99(“Georgia Lee”) - Tom Waits * Blood Money (Anti/Epitaph)

02(“Misery Is The River Of The World,” “Everything Goes To Hell,”

“Another Man’s Vine,” “Knife Chase,” “Calliope”) - Tom Waits * Alice (Anti/Epitaph)

02(“Everything You Can Think,” “Kommienezuspadt,”

“Poor Edward,” “We’re All Mad Here,” “Reeperbahn”) - Willard Grant Conspiracy * Flying Low (Slow River) 98(“The Smile At The Bottom Of The Ladder,” “St. John Street,”

“Bring The Monster Inside”) - Willard Grant Conspiracy * Mojave (Slow River) 99(“How To Get To Heaven,” “Cat Nap In The Boom Boom Room”)

- Willard Grant Conspiracy * Everything’s Fine (Slow River)

01(“Ballad Of John Parker”) - Shannon Wright * Maps Of Tacit (Quarterstick) 00(“Leaves Of Pales,” “Ribbons Of You,” “Dirty Facade,”

“Regulation Starter”) - Shannon Wright * Dyed In The Wool

(Quarterstick) 01(“The Hem Around Us,” “Vessel For A Minor Malady,” “Dyed

In The Wool,” “Method Of Sleeping,” “Surly Demise,”

“Colossal Hours,” “The Sable”) - Neil Young * Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere (Reprise)

69(“Down By The River,” “Cowgirl In The Sand”) - Neil Young * Time Fades Away (Reprise) 73

- Neil Young * On The Beach (Reprise) 74(“Vampire Blues,” “On The Beach”)

- Neil Young * Tonight’s The Night (Reprise) 75(“Tonight’s The Night,” “Albuquerque”)

- Thalia Zedek * Been Here &

Gone (Matador) 01(“Dance Me to the End of Love,” “Desanctified (Full Circle),”

“10th Lament”)

April 12, 2024

The School of Post-Punk – Class of ’83

March 29, 2024

Fester’s Lucky 13: 1994

February 29, 2024

Best of 1984